Description

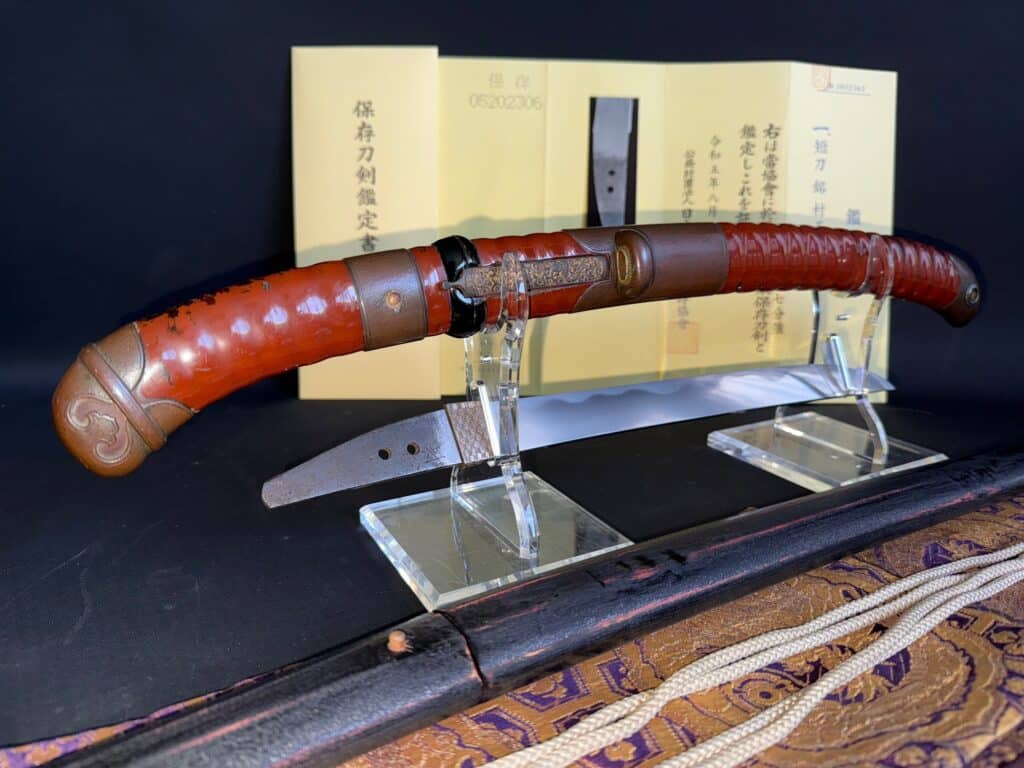

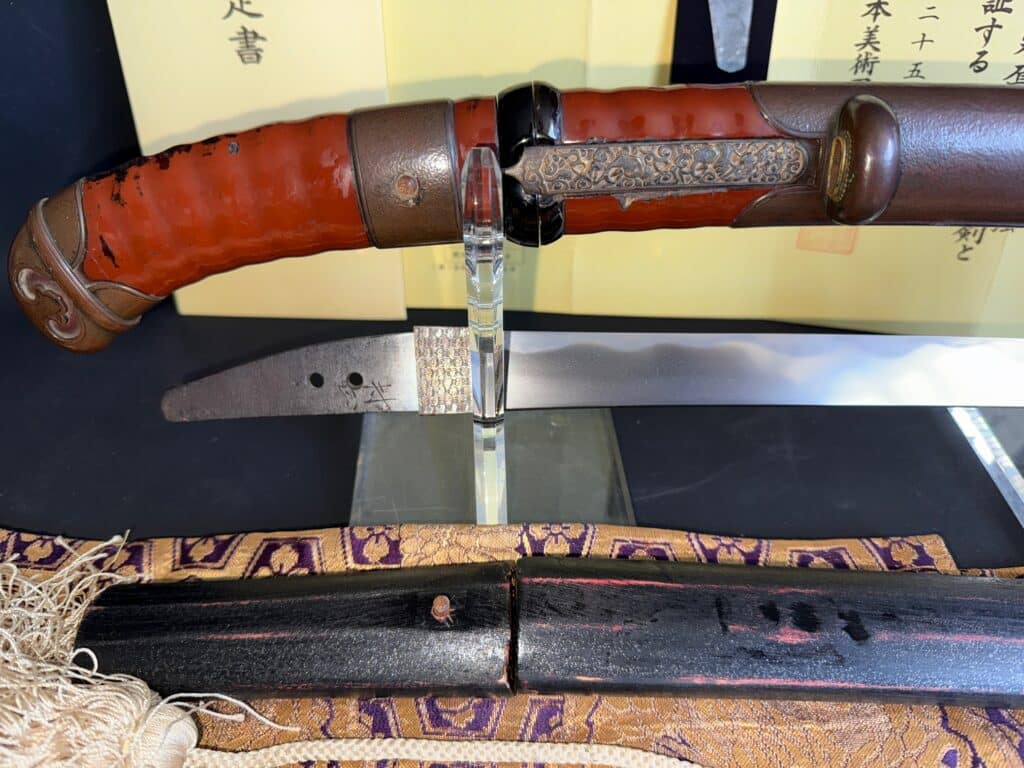

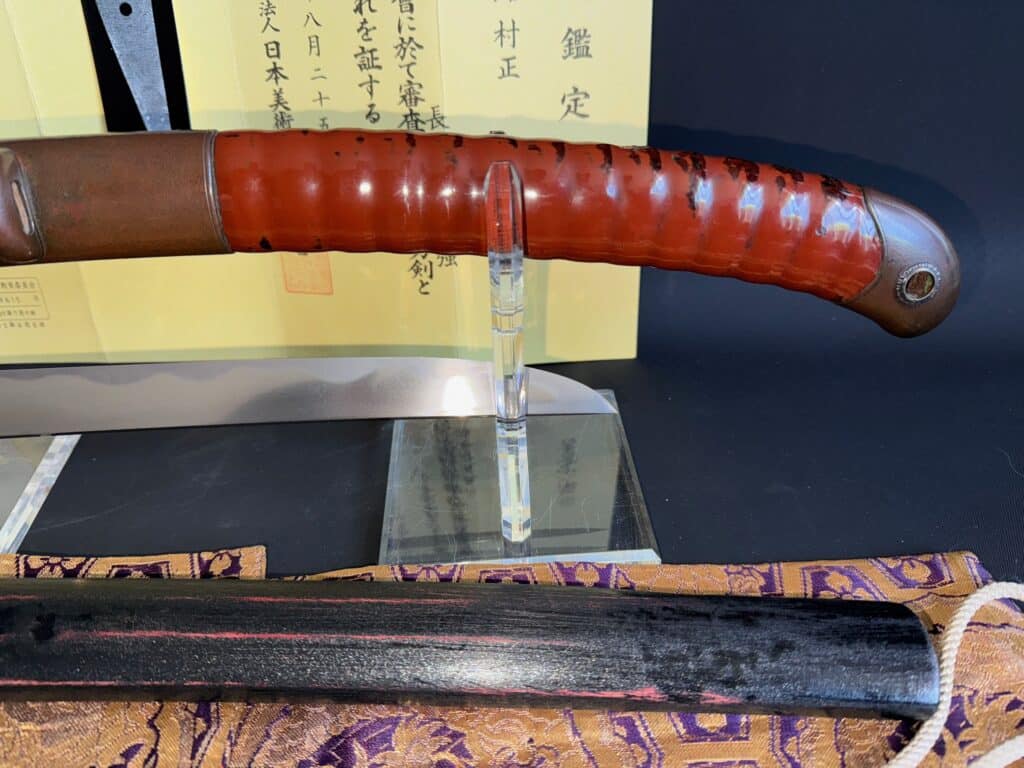

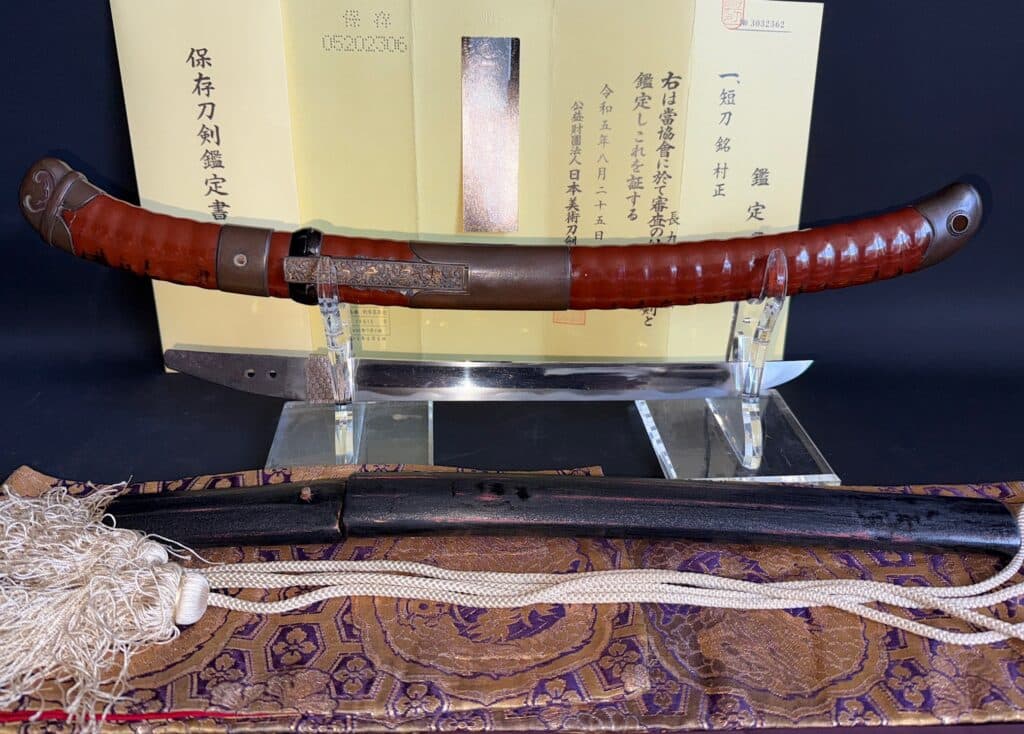

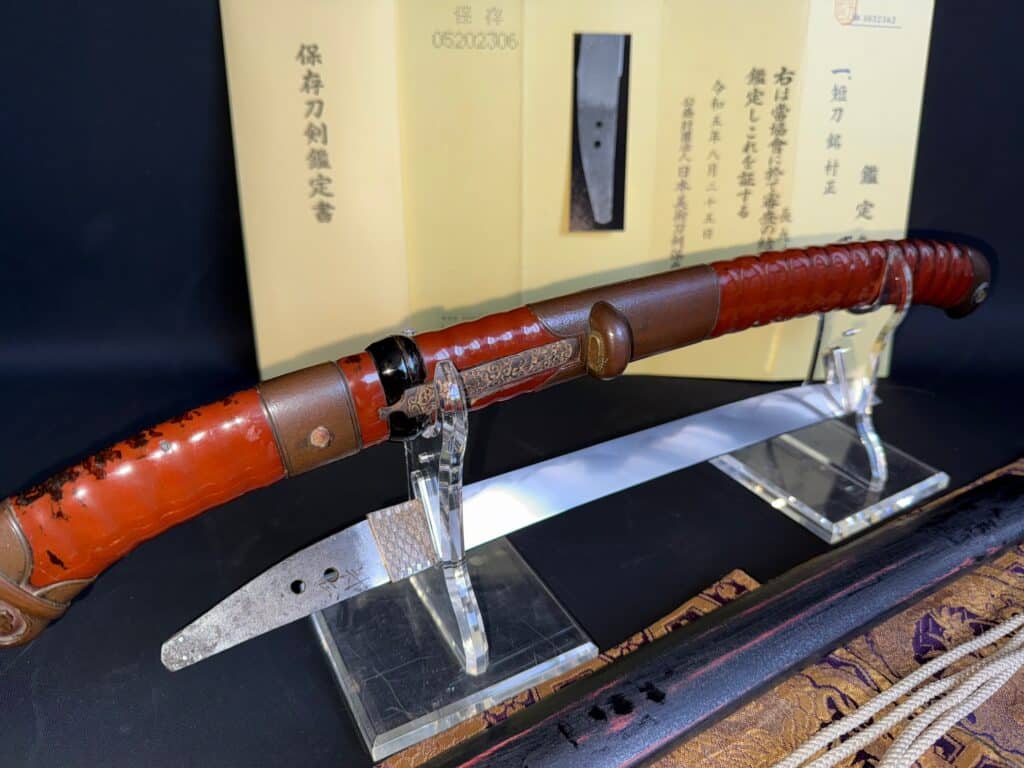

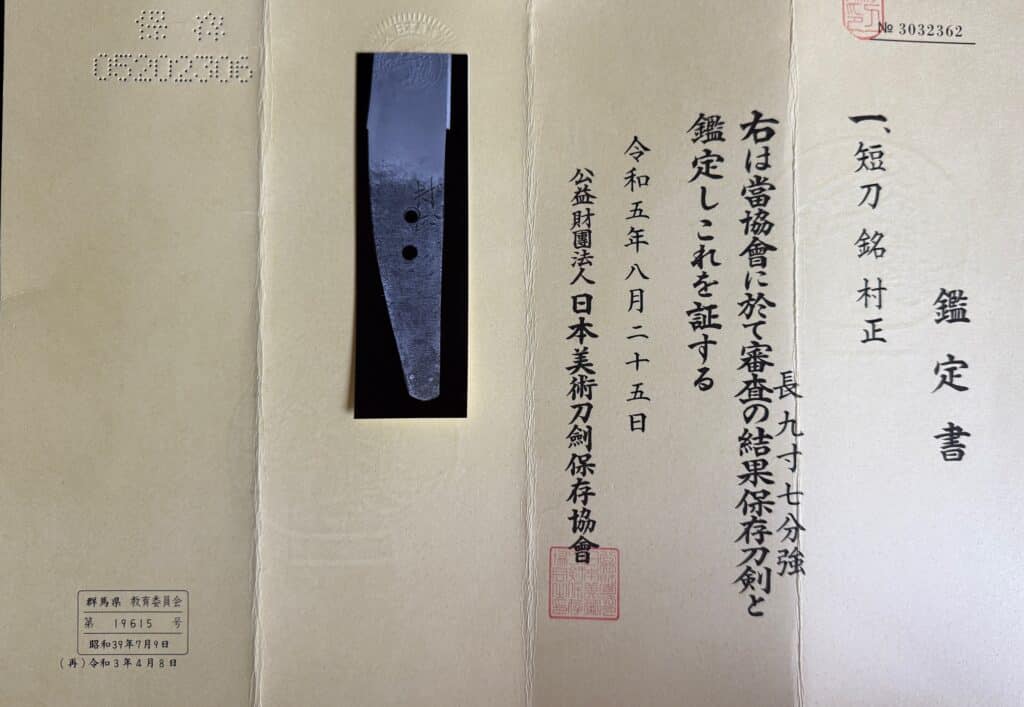

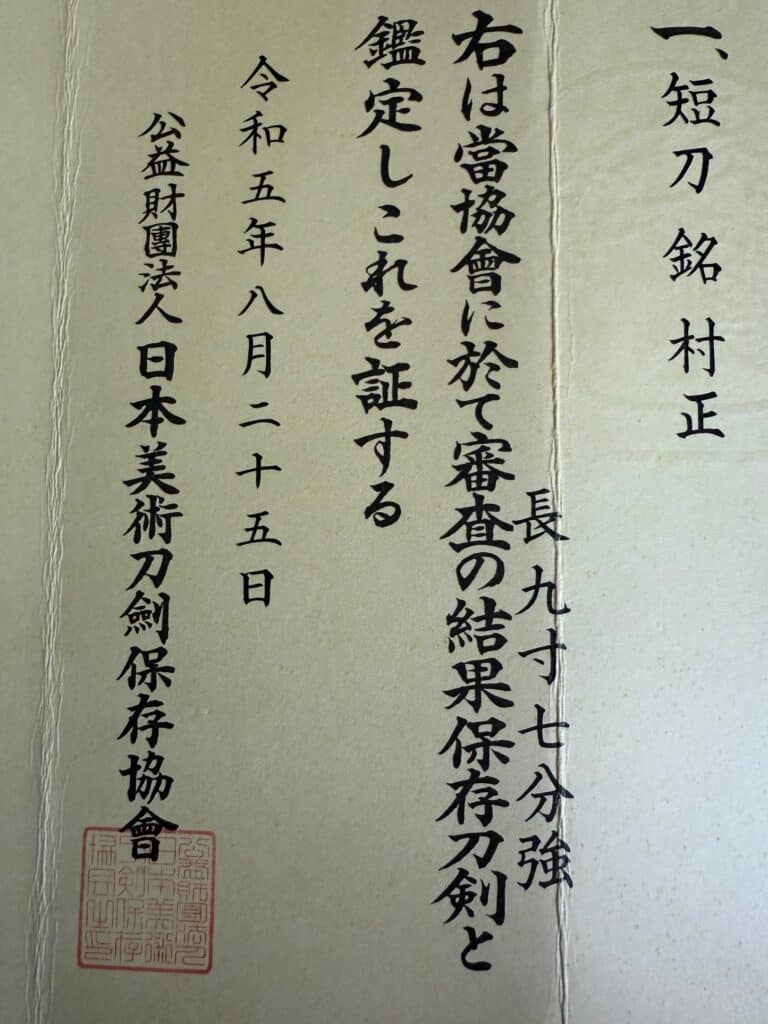

Muramasa Tanto

Attributed to Sengo Muramasa

Muromachi Period (1336–1573)

Blade Length: 28.4 cm | Weight: 162 g

Forged steel, with visible hamon and bohi (blood groove)

The tanto on display is attributed to Sengo Muramasa, one of the most enigmatic and skilled swordsmiths in Japanese history. Working during the Muromachi period, Muramasa became famed for producing blades of extraordinary sharpness and resilience—qualities that made his swords both revered and feared. This particular tanto, or short blade, exemplifies the craftsmanship, balance, and lethal elegance associated with his name.

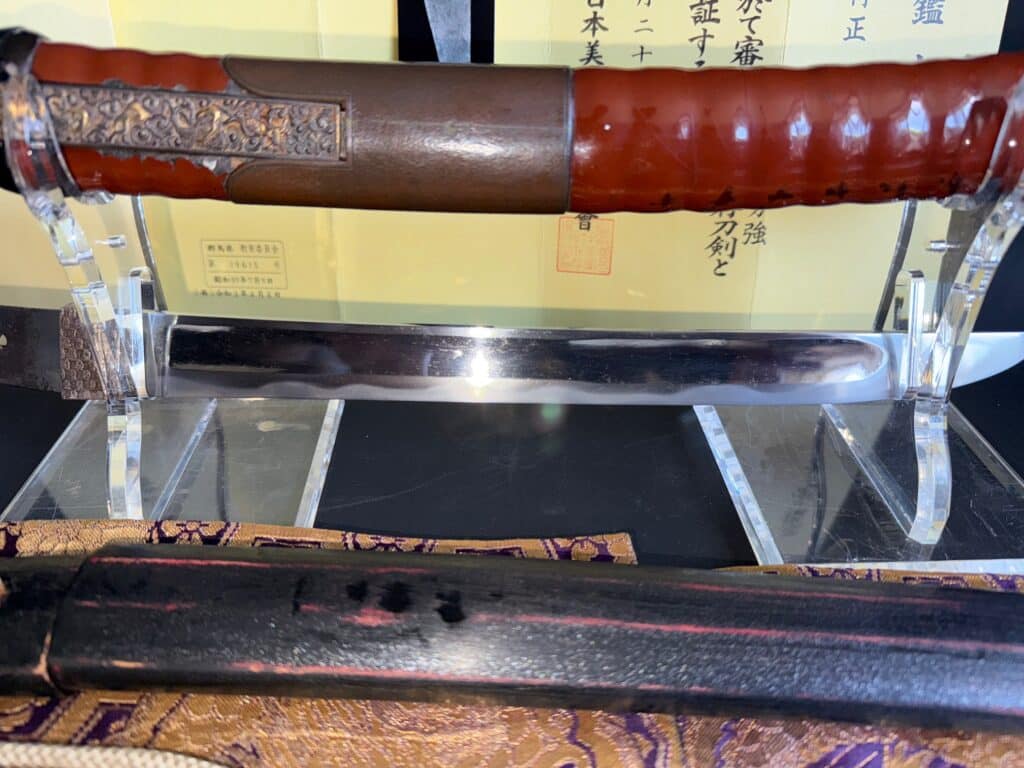

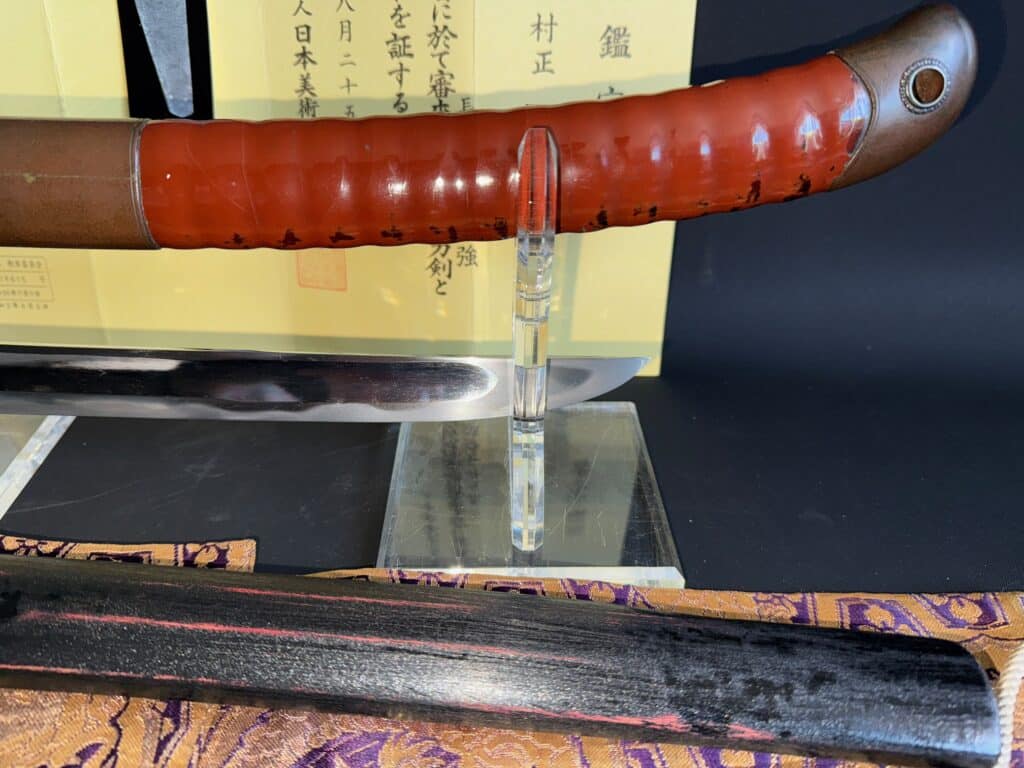

Technical Features and Craftsmanship

Measuring 28.4 centimeters in length and weighing 162 grams, the blade is perfectly proportioned for close-combat engagements. It features a bohi, or blood groove, which serves both a practical and aesthetic function—lightening the blade while enhancing its visual line. Most striking is the blade’s hamon, the temper line created by traditional Japanese differential hardening. The hamon is not merely decorative; it is a record of the smith’s precise control over temperature and metallurgy, giving the blade both flexibility and a razor-sharp edge.

The Legend of Muramasa

More than a craftsman, Muramasa is a figure of legend. His name has become synonymous with cursed blades, fueled by stories of swords that demanded bloodshed or drove their wielders to madness. Some believe that Muramasa’s forging process imbued his swords with a restless or malevolent spirit. These tales were amplified during the Tokugawa shogunate, when it was rumored that Muramasa swords had been involved in the deaths of Tokugawa family members. As a result, his blades were officially banned for a time, cementing their reputation as forbidden objects of power.

Cultural and Historical Significance

Despite—or perhaps because of—this ominous reputation, Muramasa blades have been treasured through the centuries. They occupy a unique space in Japanese history as both objects of fear and admiration. The craftsmanship of this tanto reveals not only the technical mastery of its maker but also the philosophical depth of Japanese swordsmithing, where blades are seen as extensions of the warrior’s soul.

Today, this Muramasa Tanto is revered not only as a weapon, but as a work of art and cultural icon, offering a window into the martial traditions, spiritual beliefs, and artistic sensibilities of medieval Japan. Its enduring mystique continues to fascinate historians, collectors, and martial artists around the world.

The Cursed Legacy of Nidai Muramasa (二代村正)

Any study of the second generation Muramasa smith—known as Nidai Muramasa (二代村正)—would be incomplete without first addressing the historical lore that envelops his work. For centuries, the blades of Nidai Muramasa have been regarded not merely as masterful weapons, but as objects of ill omen, particularly in relation to the Tokugawa family, the ruling shogunate of Japan for over 250 years.

These swords acquired a reputation for malevolent supernatural influence, said to bring misfortune, violence, and death to those who possessed them—especially members of the Tokugawa clan. This belief runs counter to traditional Japanese views of the sword (katana) as a sacred instrument. Typically, swords were revered as divine tools, forged from the elemental forces of fire, water, iron, wood, and earth—symbols of protection, valor, and spiritual purity.

However, for the Tokugawa, Muramasa’s swords were anything but protective. The legend of their cursed nature is rooted in a number of historical incidents that occurred during the Sengoku (戦国時代) and Edo (江戸時代) periods, which reinforced the Tokugawa perception of these blades as ominous.

The most notable early incident occurred in Tenbun 4 (1535), when Matsudaira Kiyoyasu (松平清康), the grandfather of Tokugawa Ieyasu (徳川家康), was assassinated at the age of 25 by his own retainer, Abe Masatoyo, wielding a Muramasa-forged katana. A decade later, in Tenbun 14 (1545), Ieyasu’s father, Matsudaira Hirotada (松平広忠), was gravely wounded by a Muramasa wakizashi in the hands of a drunken samurai named Iwamatsu Hachiya.

These violent encounters—each linked to a Muramasa blade—cemented a pattern in the Tokugawa psyche. Over time, Muramasa swords became taboo within the Tokugawa inner circle, their ownership discouraged or even forbidden. Despite their exceptional quality, they were viewed not as treasures but as accursed relics, capable of dooming even the most powerful of families.