Introduction to the Kabuto

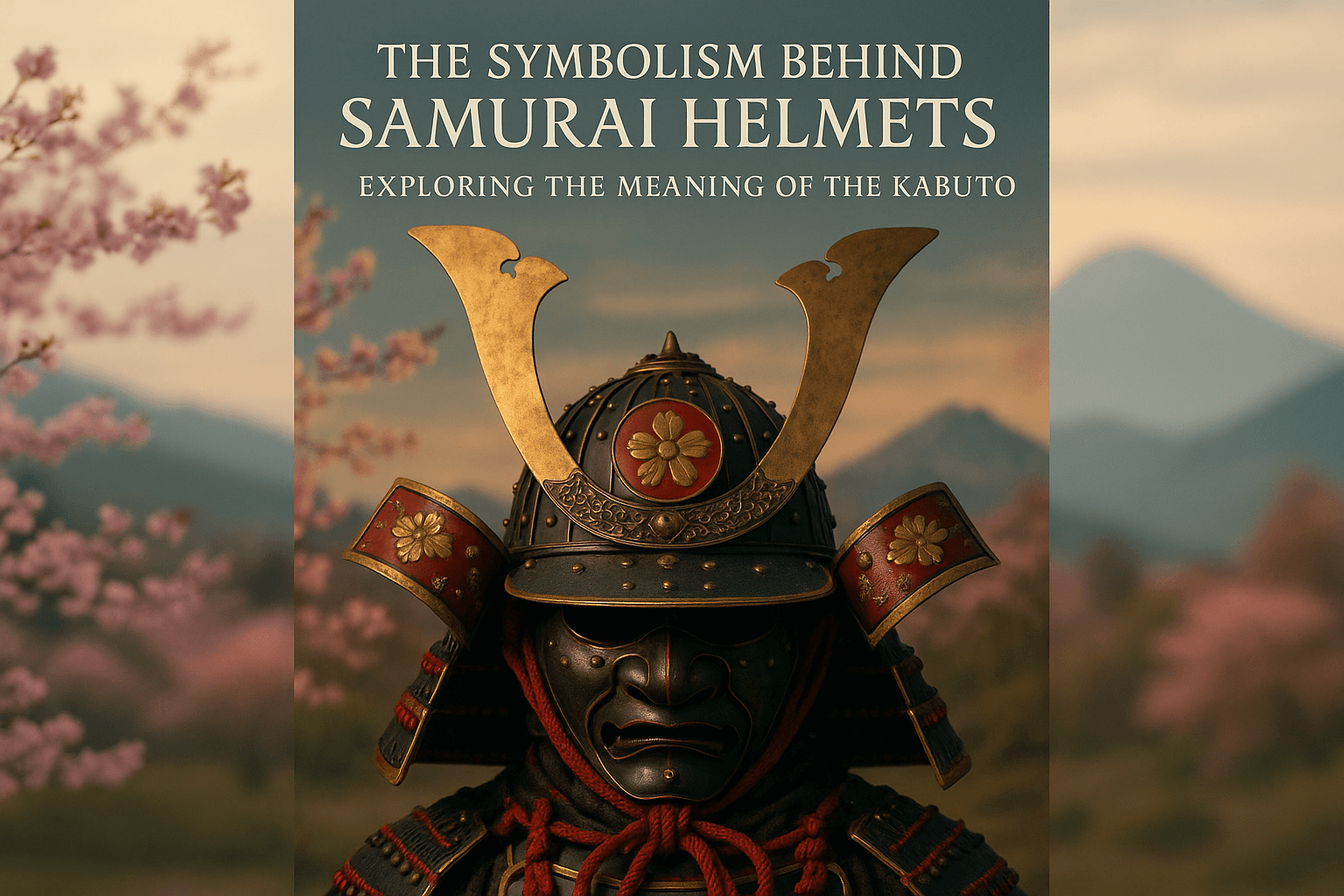

Among the most iconic elements of the samurai’s armor, the kabuto — the traditional Japanese helmet — stands as a striking fusion of function and symbolism. Originally crafted for battlefield protection, the kabuto quickly evolved into a powerful expression of identity, rank, and spiritual presence. More than mere defense gear, its elaborate designs, crest ornaments (maedate), and meticulous craftsmanship were meant to convey strength, intimidate opponents, and project the inner convictions of its wearer.

For the samurai, who lived by the fierce and disciplined bushidō code, the kabuto was both shield and statement. Adorned with mythological motifs, clan symbols, or religious imagery, each helmet told a story — not just of its owner’s martial prowess but of his place in the greater cultural and philosophical worldview of feudal Japan. In understanding the kabuto, we glimpse the heart of the samurai’s identity: a seamless blend of warrior and artist, protector and philosopher.

The Evolution of the Kabuto

The kabuto, an essential part of the samurai’s armor, evolved significantly over the centuries, mirroring shifts in warfare tactics and the cultural importance of the samurai class itself. Originally designed purely for protection, early kabuto were simple iron bowl-shaped helmets, worn as practical safeguards against arrows and sword strikes during Japan’s early feudal conflicts.

As battles became more coordinated and organized—particularly during the Sengoku period (c. 1467–1603), an era marked by nearly constant military conflict—kabuto designs grew more complex. Helmets featured sturdy neck guards (shikoro), reinforced crests, and plates riveted together for durability. Functionality remained top priority, but commanders also began distinguishing themselves through ornate additions, seeking not only protection but visibility and command presence on the chaotic battlefield.

By the Edo period (1603–1868), when peace largely prevailed under Tokugawa rule, kabuto transitioned further toward elaborate expressions of status and identity. Though still technically combat-ready, many helmets became visual statements—embellished with exaggerated crests (maedate), symbolic motifs, and lacquered finishes. Designs often referenced mythological creatures, Buddhist symbols, or clan emblems, reflecting the wearer’s values, lineage, or spiritual beliefs.

Thus, the kabuto’s journey from battlefield necessity to emblem of honor and identity mirrors the broader transformation of the samurai—from warrior to symbol of Japan’s martial, moral, and aesthetic ideals.

Materials and Craftsmanship

The creation of a kabuto was as much a reflection of a samurai’s identity as it was a feat of engineering. Master armorers combined practicality with profound symbolism, carefully selecting materials and design elements to serve both protective and expressive purposes. Iron and steel formed the core of the helmet’s defense, often layered and riveted to maximize durability while allowing flexibility in battle. High-ranking samurai might incorporate gilded copper, lacquer coatings, or even precious metals to convey status and clan allegiance.

Equally crucial was the craftsmanship behind each kabuto. From the flaring curve of the shikoro (neck guard) to the crest-bearing maedate, every detail was intentional. Artisans embedded meaning deeply into ornamentation—family crests, mythological figures, or abstract motifs signaled virtues like courage, loyalty, and wisdom. Lacquer finishes not only protected the helmet from the elements but also gave it a distinctive luster, enhancing its ceremonial presence.

Kabuto-making was a revered tradition, passed down for generations. The fusion of functional materials with symbolic artistry ensured every helmet was not just armor but a powerful narrative of the warrior who wore it.

Crests and Ornaments: The Maedate

In the striking silhouette of a samurai kabuto, one detail often demanded the most attention—the maedate, an ornate crest adorning the front of the helmet. More than just decorative flourishes, maedate served as powerful visual identifiers that conveyed the samurai’s clan allegiance, spiritual beliefs, and personal values.

These crests came in many forms: golden horns symbolizing fearlessness, stylized animals reflecting guardian spirits, or Buddhist symbols invoking divine protection. A dragon maedate might signal strength and supernatural favor, while representations of the rising sun or lotus flower could indicate enlightenment and renewal. Each choice was deeply intentional, projecting the wearer’s inner convictions to allies and enemies alike.

Family crests (kamon) were also integral, reinforcing hereditary prestige and loyalty. During battles, these emblems acted like banners on the battlefield, distinguishing friend from foe amid the chaos.

But maedate weren’t merely heraldic—they were statements of individuality in a deeply hierarchical society. Some samurai even commissioned custom symbols that fused religious imagery with personal mythology, transforming their helmets into wearable philosophies.

In essence, the maedate crowned the kabuto not just with splendor, but with a silent language of identity, belief, and pride.

Spiritual Protection and Inner Meaning

Beyond its role as physical armor, the kabuto served as a profound spiritual talisman for the samurai. Rooted in the warrior’s code of Bushidō, the helmet symbolized more than mere battlefield prowess—it represented inner resolve, courage, and an unwavering commitment to duty.

Many kabuto featured intricate designs intended to invoke protective deities or mythical creatures, such as dragons or Shintō kami, believed to guard the wearer from both physical and spiritual harm. These motifs weren’t decorative flourishes—they were visual prayers, etched in metal and lacquer, to channel divine strength and safeguard the soul.

Additionally, the very act of donning the kabuto was ritualistic. It marked a transformation, allowing the warrior to mentally and spiritually prepare for battle. In this state, the samurai could transcend fear and mortality, drawing upon an inner power rooted in discipline and honor.

Thus, the kabuto was more than a helmet—it was a vessel of spiritual protection, a sacred companion that mirrored the strength of the warrior’s spirit.

Discipline, Identity, and the Warrior Code

Beyond its function as armor, the kabuto was a powerful emblem of the samurai’s inner world, mirroring the principles of bushidō—the warrior’s code that governed samurai conduct. Each helmet, often intricately adorned and meticulously crafted, was more than a protective shell; it was a public declaration of the wearer’s discipline, honor, and social identity.

The kabuto’s imposing crest (maedate) often bore symbols tied to clan lineage, spiritual beliefs, or personal virtues, reinforcing the samurai’s role as both a warrior and moral exemplar. Just as bushidō emphasized loyalty, self-control, and courage, donning the helmet was an act of ritual and resolve—an outward expression of internal mastery. It reminded both the samurai and those who saw him of the lifelong commitment to live and die with dignity.

Wearing the kabuto was not merely preparation for battle; it was an affirmation of one’s place within the rigid hierarchy of feudal Japan. In this way, the helmet became a fusion of function and philosophy—a silent, steadfast witness to the deeply disciplined soul beneath the steel.

Legacy and Modern Resonance

The kabuto, once a fearsome piece of battlefield armor, now stands as a powerful emblem of courage, discipline, and cultural heritage. Its legacy extends far beyond the samurai era, resonating in present-day Japan through both tradition and contemporary expression.

In martial arts like kendo, practitioners don protective headgear inspired by the kabuto, merging function with reverence for ancient warrior values. The helmet’s form and symbolism serve as a bridge connecting modern sportsmanship with the samurai’s code of honor—bushidō—instilling discipline and mental fortitude.

Culturally, the kabuto is a centerpiece in celebrations like Children’s Day (Kodomo no Hi), where miniature replicas are displayed to inspire strength and virtue in young boys. It functions as more than decoration; it’s a reminder of noble ideals passed from one generation to the next.

Globally, the kabuto has become an icon of Japanese history that fascinates collectors, historians, and artists alike. Museums worldwide feature them not only for their ornate craftsmanship but as symbols of a complex warrior ethos that continues to inspire literature, film, and fashion.

In this way, the kabuto’s story endures—not as a relic of war, but as a timeless symbol woven into the cultural fabric of Japan and admired across the world.