The Way of the Warrior

For the samurai, discipline wasn’t limited to swordsmanship—it shaped every aspect of their existence. This unwavering commitment to control, precision, and inner strength was known as Bushidō, the Way of the Warrior. More than a martial code, Bushidō was a comprehensive ethical guide defining honor, loyalty, humility, and the pursuit of personal perfection.

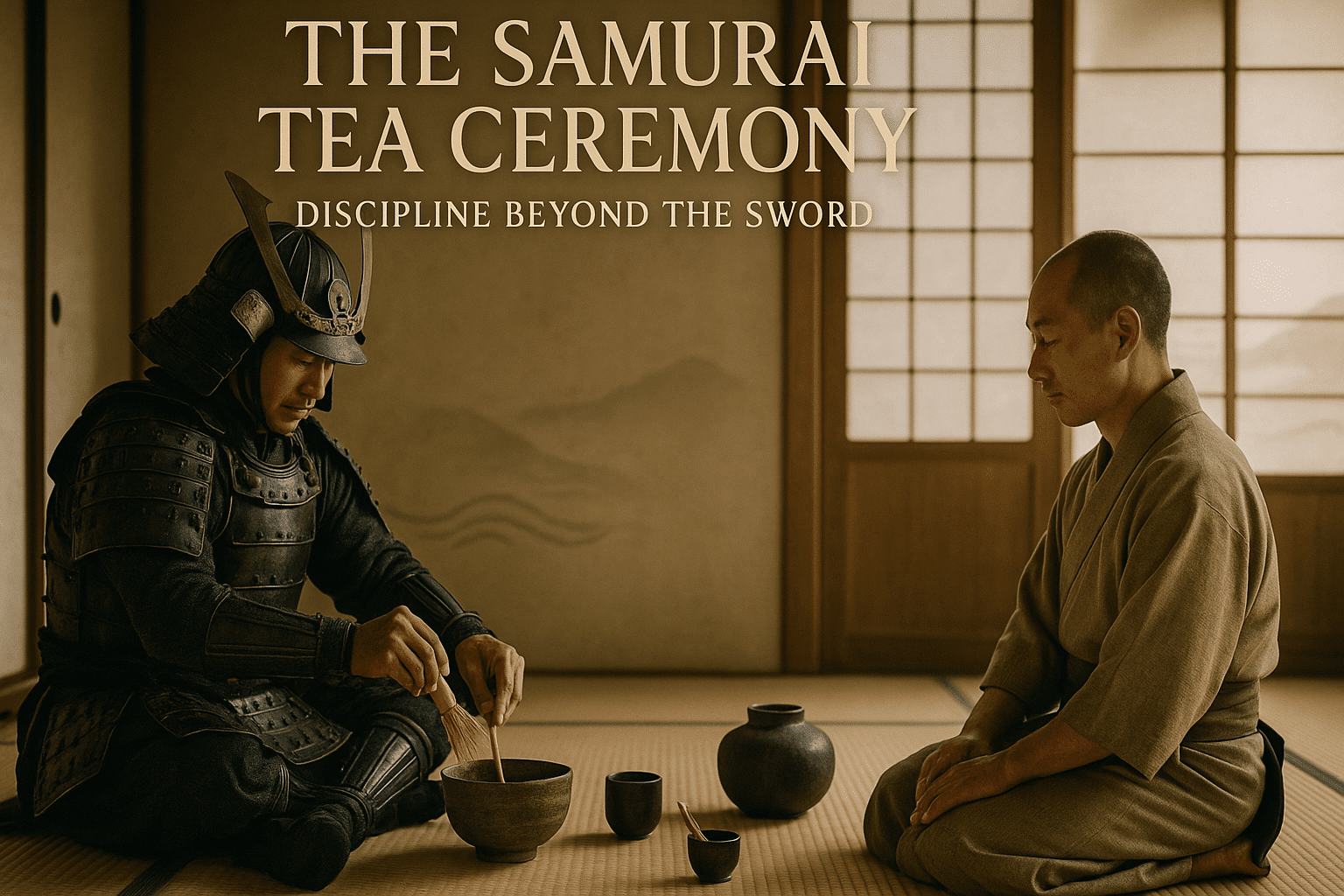

Training lasted a lifetime, encompassing not only combat techniques but also calligraphy, poetry, and philosophy. The samurai honed their minds as diligently as their blades, believing that true mastery required harmony between body and spirit. Daily rituals were carried out with meticulous care, whether it was polishing armor, bowing in respectful greeting, or attending to the quiet formality of a tea gathering.

In this balanced lifestyle, every action was a reflection of inner discipline. Even the seemingly simple act of preparing and serving tea became a battlefield of its own—one of patience, presence, and precision. The samurai understood that victory did not always lie in defeating an opponent but often in conquering the self. Through this lens, the tea ceremony emerged not as a diversion from warfare, but as an extension of the warrior’s path.

Tea and Steel: A Historical Bond

Amid the chaos of Japan’s Warring States period (1467–1615), where warlords vied for power and the clash of blades echoed daily, the tea ceremony—known as chanoyu—emerged as an unlikely companion to the way of the samurai. Far from being a mere act of leisure, the ritual of preparing and serving tea became a meditative practice that mirrored the values at the core of Bushidō: discipline, humility, and inner stillness.

The origins of tea culture in Japan trace back to the introduction of powdered green tea (matcha) by Zen Buddhist monks in the 12th century. By the 15th and 16th centuries, as Japanese feudal lords (daimyō) increasingly aligned with the aesthetics of Zen, samurai warriors followed suit. They found in tea not only spiritual resonance but also strategic utility: the tearoom became a sanctuary for reflection, diplomacy, and even the quiet vow before battle.

One of the most influential figures in linking tea with samurai culture was Sen no Rikyū, the 16th-century tea master who codified the principles of wabi-sabi—finding profound beauty in simplicity and imperfection. Rikyū’s austere style of tea, stripped of extravagance, resonated with war-hardened samurai leaders like Oda Nobunaga and Toyotomi Hideyoshi, who hosted tea gatherings not only as cultural affairs but as tools of political unification.

In this turbulent age, the samurai’s participation in tea ceremonies was more than symbolic. The quiet rituals contrasted starkly with the violence of war, offering moments of clarity and control. In the act of purifying utensils, preparing tea, and serving a guest, the warrior practiced mental precision and respect—disciplines as vital off the battlefield as on it.

Thus, the bond between tea and steel was forged not in contradiction, but in complement. The tea ceremony, far from softening the samurai spirit, sharpened it—tempering aggression with introspection, and transforming the art of war into a path of harmony.

Ritual as Training

In the world of the samurai, the tea ceremony was not a departure from martial discipline—it was an extension of it. Every gesture, from the folding of the fukusa (silken cloth) to the precise pouring of water, mirrored the kata practiced in swordsmanship. These actions, while seemingly mundane, were infused with intent and mindfulness, training the warrior’s mind just as much as his body.

The tea room, or chashitsu, functioned as an arena of refinement and composure. Within its confined space, the samurai honed their awareness, focusing entirely on the present. The ritual demanded the same presence of mind required on the battlefield: calm under pressure, clarity of movement, and unshakable focus.

Beyond refining etiquette, the tea ceremony fostered patience and humility. In contrast to the flash of combat, tea demanded quiet mastery—an inward control that sharpened the warrior’s readiness without the need for a drawn blade. In this sense, practice in the tea room became just as crucial as time spent in the dojo. Ritual was not a break from training—it was training.

The Dojo Becomes a Tearoom

In the quiet harmony of the tearoom, the samurai found a reflection of the dojo. Both were spaces stripped of excess, where discipline was internalized through practice and presence. The tearoom, with its muted tones and deliberate rituals, demanded the same mindfulness as drawing a blade—the same attentiveness to breath, movement, and the unspoken rhythm of life.

Stepping into the tearoom was akin to entering the training hall. Shoes were left at the entrance, along with ego and distraction. Just as the dojo instilled patience through repetitive katas, the tea ceremony unfolded through carefully choreographed motions—each gesture an embodiment of humility and control. The act of whisking tea was no less focused than the arc of a sword; both required precision honed through quiet perseverance.

Here, strength was measured not in combat but in composure. The warrior’s posture in the tearoom, knees folded in seiza, back straight, eyes lowered, spoke of the same resilience forged in battle. By immersing themselves in this contemplative space, samurai cultivated an emotional fortitude that complemented their martial prowess—learning to temper action with stillness, reaction with reflection.

In essence, the tearoom became another kind of dojo—one where the opponent was the self, and victory meant mastering the moment.

Utensils and the Unseen Blade

In the quiet elegance of the samurai tea ceremony, every utensil carries a weight far beyond its function. The bamboo ladle (hishaku), used to transfer water with steady grace, becomes a symbol of self-restraint and mindfulness—qualities central to a warrior’s code. Like drawing a blade, each movement is deliberate, echoing the discipline honed on the battlefield.

The tea whisk (chasen), fragile yet vital, reflects a harmonious balance between strength and subtlety. In the warrior’s hands, this delicate implement channels years of rigorous training into a simple act—whipping tea with precision and harmony. Just as swords are extensions of the warrior’s spirit, these humble tools become vessels of intent, emphasizing clarity of purpose and unity of body and mind.

Even the cleaning of utensils takes on a ritualistic solemnity akin to the maintenance of a katana. Purity, both of tool and soul, is essential. The disciplined gestures mirror martial kata—forms passed down through generations—not for combat, but for self-mastery. In these rituals, the swordsman lays down his weapon but not his principles, letting the tea room become a different kind of dojo. Through these instruments of serenity, the samurai channels the same resolve, poise, and reverence demanded by the art of war.

Mind Like Still Water

In the disciplined life of a samurai, mastery of the sword was inseparable from mastery of the self. The tea ceremony, or chanoyu, provided a sacred space where the clamor of the battlefield gave way to the stillness of contemplation. Within the tatami-lined tea room, each motion—every bow, pour, and turn of the wrist—became an exercise in mindfulness, stripping away distraction and anchoring the practitioner in the present moment.

This ritualistic simplicity served a profound purpose: to still the turbulent waters of the mind. By focusing fully on the meticulous preparation and offering of tea, the samurai cultivated heijoshin—a state of undisturbed mental equilibrium. Like water undisturbed by wind, a calm mind reflects the world clearly, free of distortion or fear. In this clarity, the samurai found readiness for all outcomes, including the inevitability of death.

The tea ceremony was not an escape from mortality but an embrace of it. Surrounded by the transience of wabi-sabi aesthetics—the fading flower, the weathered cup—the samurai was reminded that beauty lies in impermanence. From this awareness emerged a quiet strength: a readiness grounded not in aggression, but in stillness.

Discipline Without Glory

In the stillness of a morning, before blades are drawn or strategies devised, a samurai may be found tending to the quiet art of tea. No fanfare announces this ritual. No audience applauds. Yet in the soft clink of porcelain and the careful folding of cloth, there echoes the same discipline that governs the battlefield.

True mastery, the samurai understood, is not a sudden blaze of brilliance. It is nurtured in repetition, in silence, in the invisible shaping of one’s spirit through routine. Preparing tea—precisely, peacefully—is a form of practice no less demanding than martial kata. It teaches presence, restraint, patience.

The tea ceremony offered a daily encounter with impermanence and control—two forces every warrior must learn to balance. By pouring focus into a fleeting moment, the samurai sharpened a keener blade within: one forged in humility and refined in purpose.

Discipline without glory is the kind that endures. It does not seek applause; it seeks alignment. In honoring the smallest rituals with the greatest care, the samurai left us a legacy beyond combat—an invitation to cultivate grace in all that we do, whether seen or unseen.