Introduction: Armor as a Reflection of Discipline

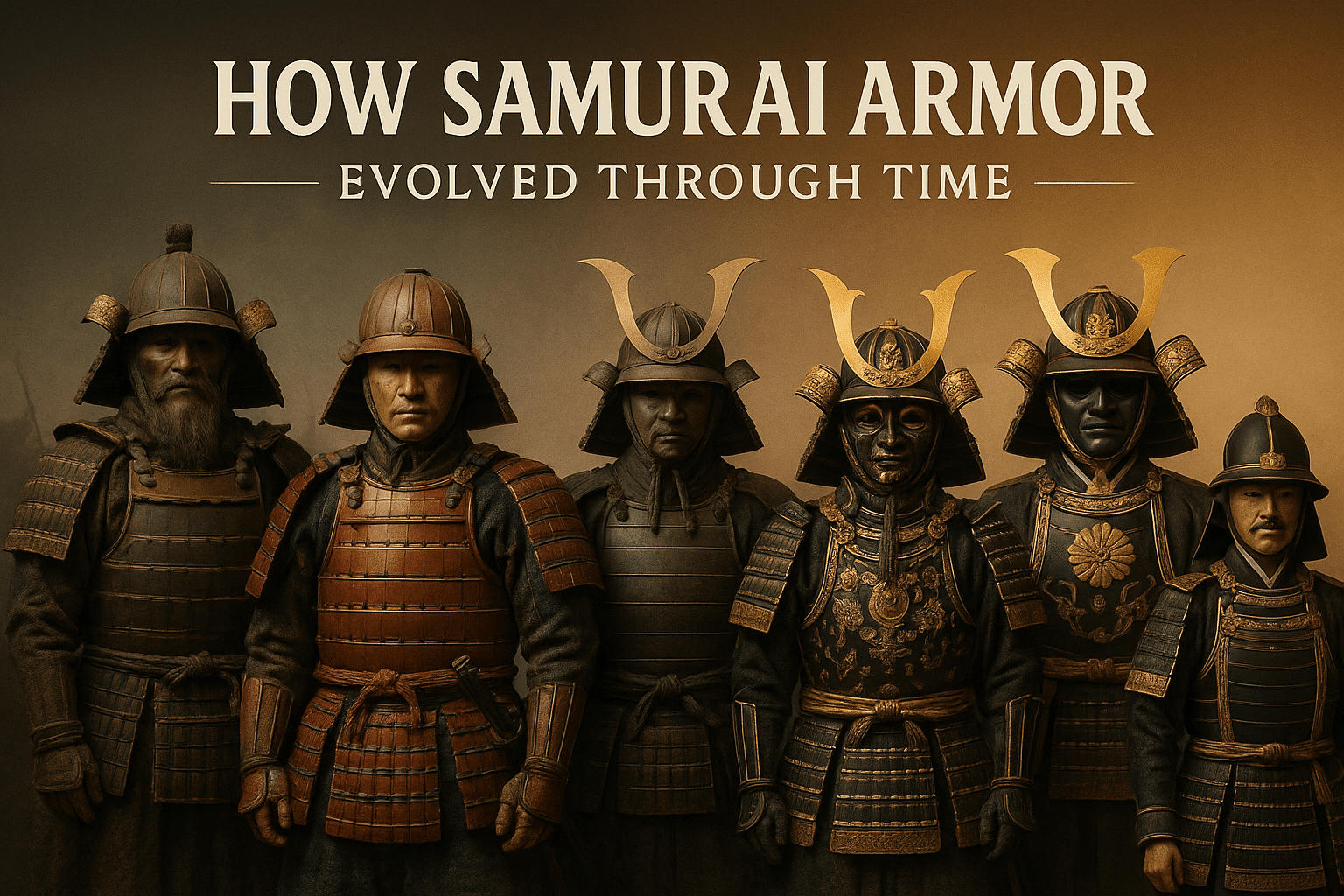

In the world of the samurai, armor was never just mere protection—it was a powerful expression of the warrior’s inner code. Every lacquered plate and every woven cord told a story of unwavering discipline, honor, and personal identity. More than a tool of war, samurai armor embodied bushidō, the “way of the warrior,” serving as a visual testament to a life governed by loyalty, courage, and self-control.

Craftsmanship was meticulous, with each suit customized not only for battle readiness but also to reflect the wearer’s social standing and clan affiliation. Colors, emblems, and construction techniques were chosen with care, reinforcing a disciplined life where appearance and function walked in lockstep. As the tides of warfare and politics shifted throughout Japanese history, the armor evolved—but its symbolic weight as a reflection of samurai values remained constant, adapting to preserve tradition while meeting the demands of the era.

The Heian Period: Beginnings of the Ō-yoroi

During the Heian period (794–1185), the foundations of traditional samurai armor took shape with the emergence of the ō-yoroi—one of the earliest and most iconic types of samurai protection. Designed primarily for mounted archers, the ō-yoroi was a grand, imposing suit of armor that reflected both the martial needs and the aesthetic sensibilities of the time.

Constructed from small lacquered iron or leather scales (kozane) laced together with colorful silk cords, the ō-yoroi was as much a work of art as it was a tool of war. Its structure was particularly suited for horseback combat, featuring a large, rigid cuirass (dō) and a distinctive, boxy skirt (kusazuri) to protect the rider’s legs and sides. The helmet (kabuto) often included a sweeping neck guard (shikoro), offering crucial protection from arrows fired during battle.

The armor’s weight and rigidity made it less than ideal for hand-to-hand combat on foot, but it served its purpose well in the elite cavalry tactics of the era. Symbolizing status and valor, the ornate design of the ō-yoroi also reinforced the growing cultural identity of the samurai class, setting the stage for more refined and functional armor in centuries to come.

Kamakura Era: The Rise of Function

With the dawn of the Kamakura era (1185–1333), Japan experienced significant political and military upheaval, most notably the rise of the samurai class and their increasing involvement in organized warfare. This shift brought about a crucial evolution in armor design—away from the ornate displays of status favored by courtly elites and toward gear optimized for battlefield effectiveness.

The primary development during this period was the refinement of the ō-yoroi, or “great armor.” Originally used by mounted warriors, the ō-yoroi featured boxy shoulder guards (sode), a large cuirass, and protective scales made from lacquered leather and iron sewn onto silk cords. As samurai faced longer campaigns and more agile enemies, the need for mobility, durability, and ease of repair became paramount.

In response, armor became increasingly modular. The do-maru, a more streamlined and wraparound style of cuirass, began to gain favor among foot soldiers due to its closer fit and improved range of motion. Overlapping lamellae were refined to better deflect arrows and sword strikes, while the helmet (kabuto) evolved with more robust neck guards and crests offering both protection and visibility on chaotic battlefields.

The Kamakura era marked a turning point, where function began to define form, setting the standard for the samurai’s enduring reputation as both a cultured elite and a hardened warrior.

Muromachi and Sengoku Periods: War Becomes Commonplace

During the Muromachi (1336–1573) and Sengoku (1467–1615) periods, Japan descended into nearly constant warfare. Regional warlords (daimyō) vied for power, fueling an era where military conflict became an everyday reality. In this volatile landscape, samurai armor underwent a dramatic transformation to meet the demands of rapid mobilization and large-scale battles.

Traditional ō-yoroi, with its ornate construction and heavy box-like structure, proved too cumbersome for the fluid and fast-paced fighting now required. As a result, armor evolved to become more practical and agile. The lighter do-maru style, originally worn by foot soldiers, gained popularity among higher-ranking samurai for its ease of movement. Eventually, new hybrid styles emerged, like the tosei-gusoku, or “modern armor,” which incorporated both traditional lamellar construction and more rigid plating for better protection and speed of fabrication.

Samurai also began favoring simpler, more modular designs that could be mass-produced and easily repaired. Components such as cuirasses, shin guards, and helmets were standardized and sometimes even reinforced with European-influenced iron plating introduced through contact with Portuguese traders and firearms.

Adaptability and mobility now defined samurai warfare, and armor followed suit—becoming a strategic advantage rather than just a symbol of status. As the battlefield evolved, so did the samurai’s protection, ushering in armor built for endurance, speed, and efficiency in a time dominated by constant conflict.

Azuchi-Momoyama Period: Art Meets Armor

The Azuchi-Momoyama period (1573–1603) marked a turning point in samurai armor design, where aesthetics joined forces with functionality in striking new ways. As Japan moved toward greater unification under powerful leaders like Oda Nobunaga and Toyotomi Hideyoshi, warfare became more consolidated, and the need for constant battle diminished. This relative peace paved the way for armor to evolve from purely utilitarian gear into a canvas for cultural expression.

Armor of this era retained its protective qualities but became notably more elaborate. The tosei gusoku (“modern armor”) design was refined for comfort and mobility, incorporating improved lacing techniques and iron-plated construction. However, what truly set Azuchi-Momoyama armor apart was its ornate decoration—gold leaf plating, lacquered surfaces, and family crests (mon) were common, turning battlefield apparel into a symbol of status and taste.

Helmets (kabuto) also became works of art, often featuring dramatic crests (maedate) shaped like antlers, horns, or religious symbols. These designs were not just for effect—they signaled a samurai’s allegiance, values, and social rank. The fusion of bold visual elements and high craftsmanship mirrored the grandeur of the tea ceremonies, Noh theater, and castle architecture flourishing in the same period.

In essence, the Azuchi-Momoyama era elevated samurai armor to a statement of identity, prestige, and cultural patrimony—demonstrating that even in times of reduced conflict, the warrior’s spirit could still be worn with power and poise.

Edo Period: From Battlefield to Ceremony

With the dawn of the Edo period in the early 17th century, Japan entered an era of relative peace under Tokugawa rule. For the samurai class, once defined by their role on the battlefield, this shift marked a profound transformation—not just in lifestyle, but in appearance. No longer required for the rigors of war, samurai armor evolved from functional battle gear into a powerful emblem of status, heritage, and ceremonial importance.

Samurai still wore armor, but its purpose centered more on prestige than protection. Elaborate designs flourished: lacquered surfaces gleamed, ornate crests (mon) symbolized lineage, and masks (menpō) took on dramatic features to convey strength and resolve. Armor became a display of a clan’s honor, worn in court rituals, parades, and official processions rather than combat.

Dō-maru and tōsei-gusoku—once engineered for battlefield agility—were now tailored to impress. Artisans infused armor with artistic expression, utilizing luxurious materials such as silk cords, gilded metals, and decorative inlays. This fusion of martial formality and aesthetic refinement reflected the samurai’s new role as bureaucrats, scholars, and cultural patrons.

In this time of peace, armor transformed into a silent storyteller—less a tool of war, more a canvas for tradition and personal identity. Its presence affirmed loyalty to the shogunate, preserved ancestral glory, and maintained the samurai’s enduring cultural relevance.

Modern Reflections: Legacy of the Samurai Spirit

Though samurai armor is no longer worn on the battlefield, its symbolism endures as a powerful reflection of Japan’s deep cultural heritage. The intricate design and function of the armor—once a matter of life and death—now serve as a visual and philosophical reminder of core samurai virtues: discipline, honor, courage, and resilience. These values resonate in modern Japan, finding expression in martial arts like kendo and iaido, where practitioners don traditional garb and adhere to strict codes of conduct that echo bushidō.

Beyond the dojo, the samurai spirit influences contemporary Japanese identity. Exhibitions, films, and festivals keep the memory of the armored warriors alive, while artists and designers draw aesthetic inspiration from the form and concept of samurai gear. In business, education, and personal development, the tenets once embodied in steel and silk continue to guide ethical behavior and inner strength.

Samurai armor, though a relic of the past, is far from forgotten. Instead, it serves as a timeless emblem of the principles that continue to shape Japan’s present and inspire its future.