Description

A Masterpiece of Edo Swordsmithing: Wakizashi by Nidai Suishinshi Masahide (Sadahide), 1816

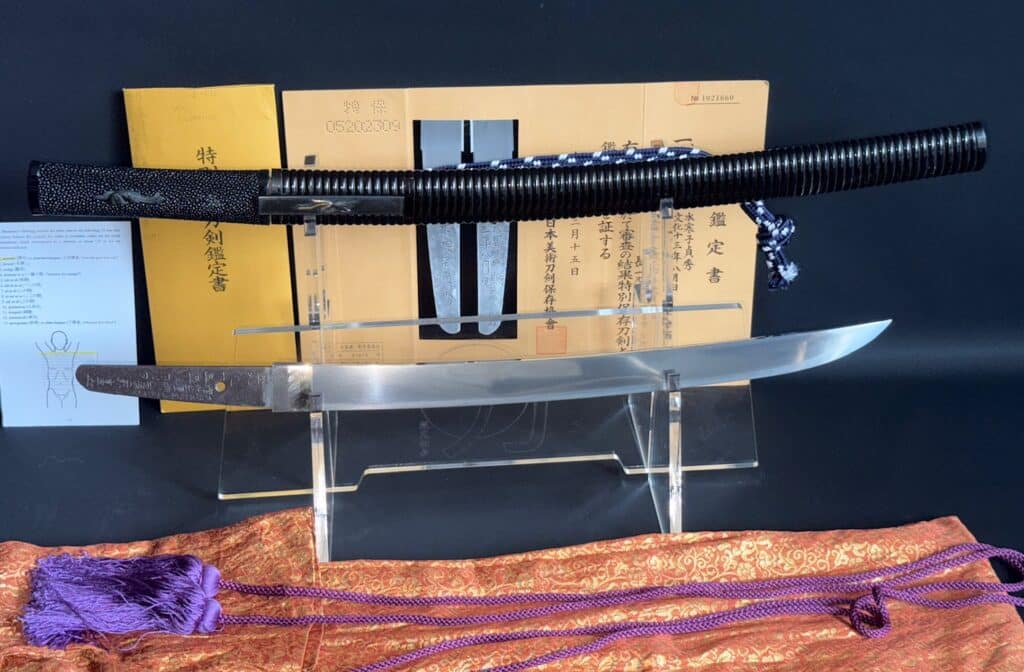

The Japanese sword (nihontō) has long been celebrated as both weapon and art. More than a mere tool of war, the sword reflects centuries of tradition, technical refinement, and cultural symbolism. Among the countless swordsmiths of Japan’s long history, the Suishinshi lineage occupies a special position, embodying the revival of classical styles during the late Edo period. This Wakizashi, forged in 1816 by Nidai Suishinshi Masahide (Sadahide), exemplifies the extraordinary craftsmanship of that tradition. It is not only a beautifully made sword but also one with documented martial testing and prestigious certification, elevating it to the level of a museum-quality artifact.

Historical Context – The Suishinshi Legacy

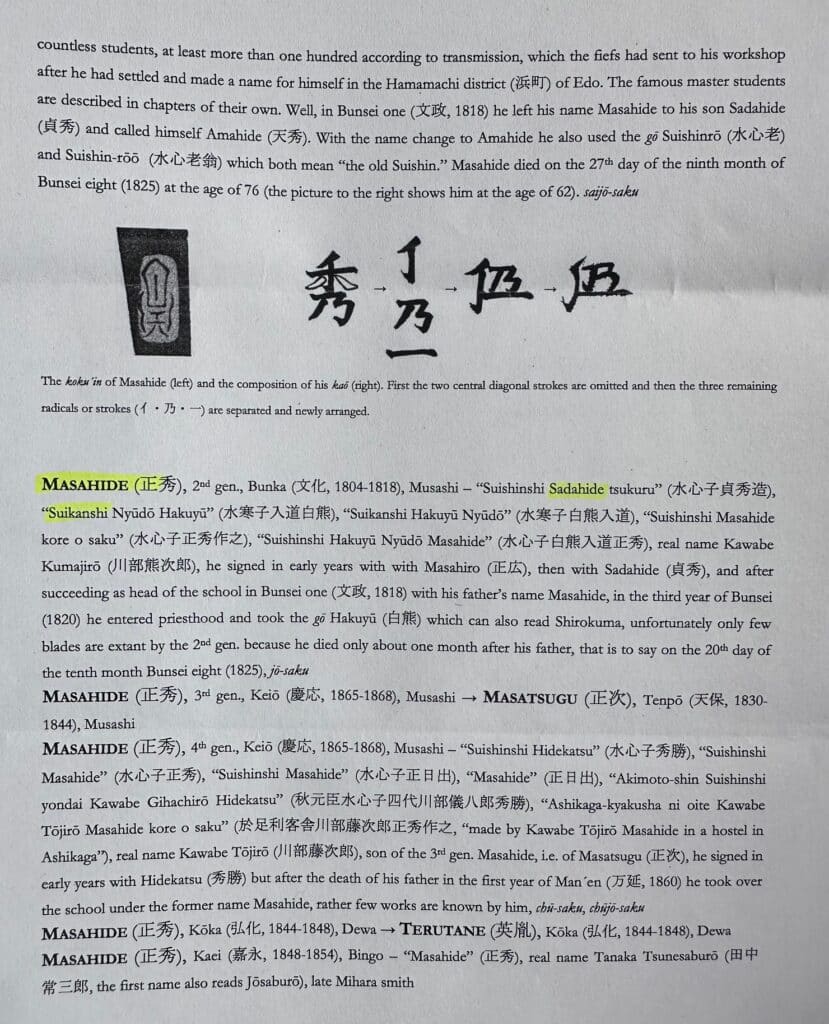

The late Edo period (1603–1868) saw a decline in active warfare but a flourishing of swordmaking as an art. With peace established under the Tokugawa shogunate, swords increasingly became symbols of rank, status, and artistry rather than battlefield necessity. Within this cultural environment, the swordsmith Shodai Suishinshi Masahide (1750–1825) spearheaded a movement to revive the classical styles of the Kamakura and Muromachi periods. His school, the Suishinshi tradition, produced works that consciously drew upon the aesthetics of earlier masters while integrating Edo-period refinements.

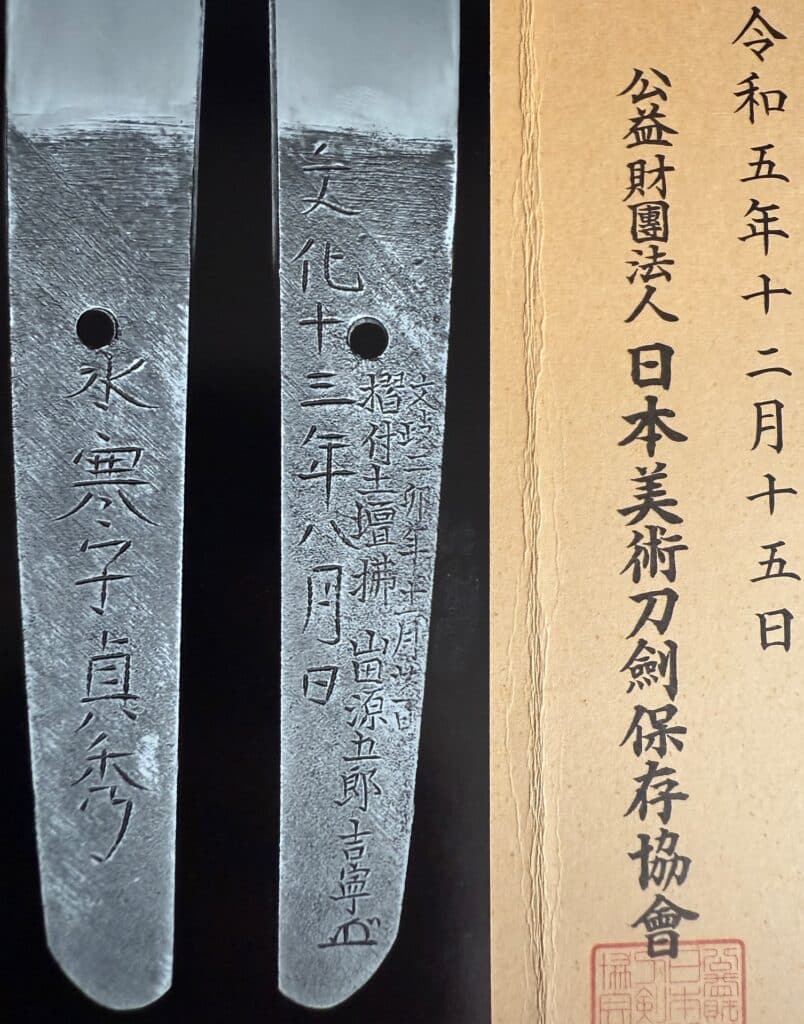

His son, Nidai Suishinshi Masahide, better known as Sadahide, inherited this mantle. Active in the early 19th century, Sadahide continued his father’s vision while forging blades that bore his own signature style. Works by Sadahide are prized for their high technical quality, careful forging, and artistic hamon patterns. His swords, much like those of his father, were sought after by samurai, connoisseurs, and scholars alike.

Blade Characteristics

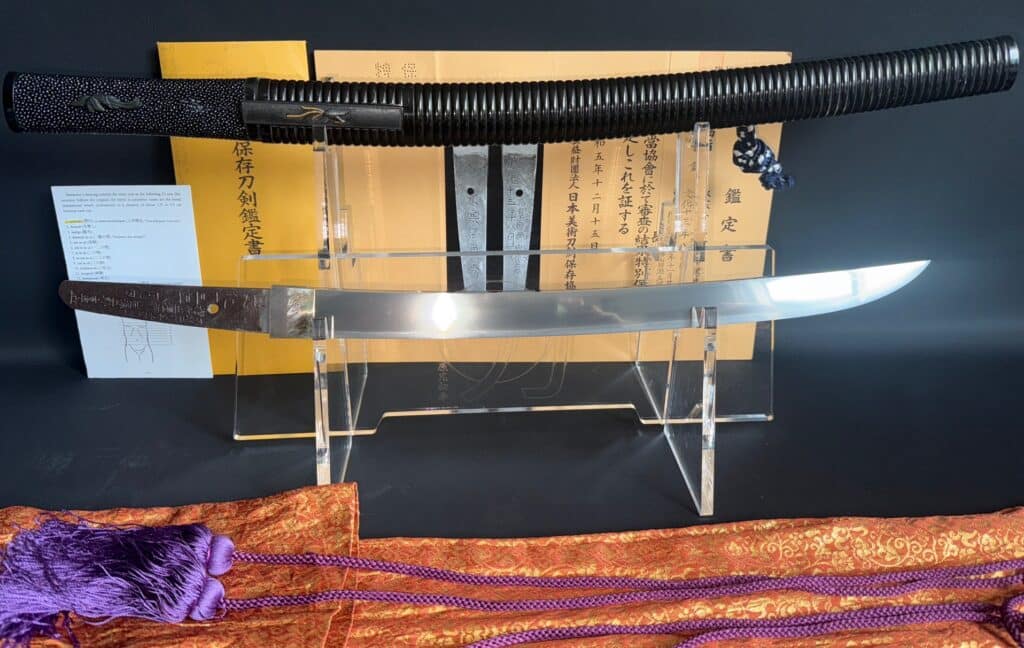

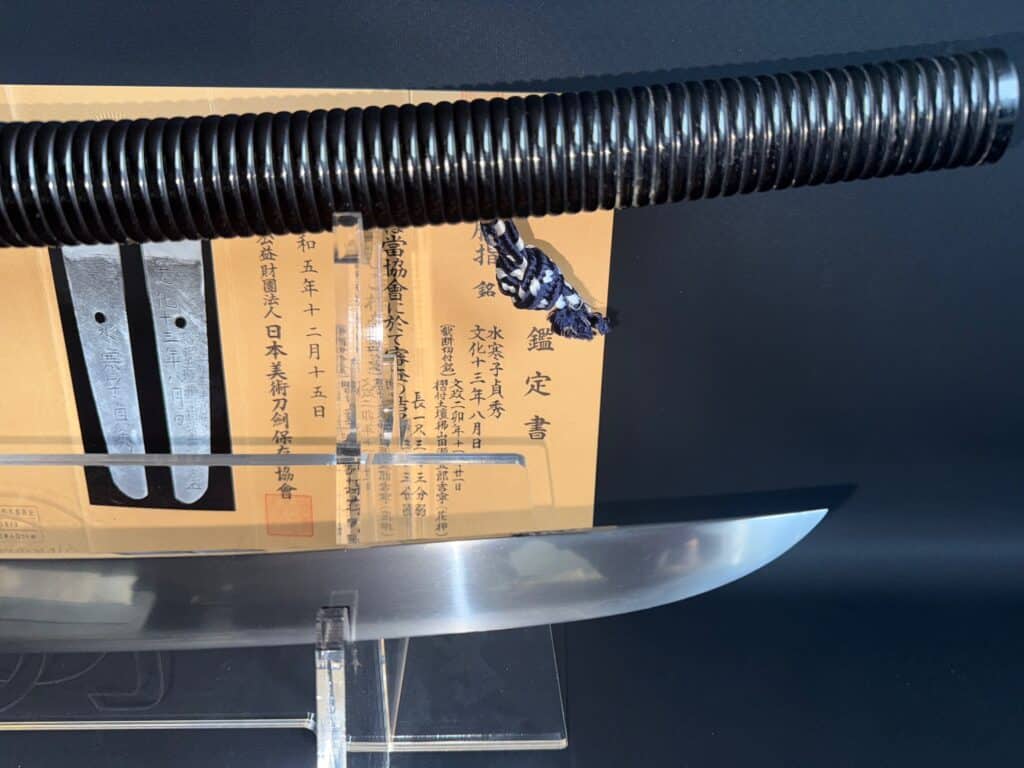

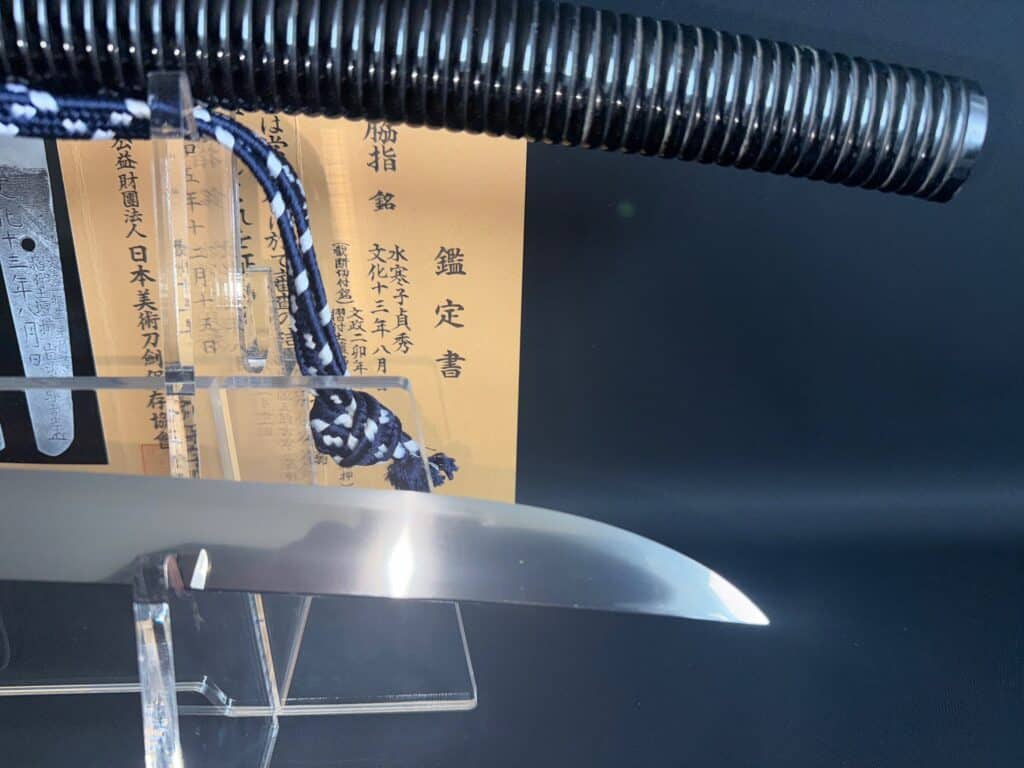

This Wakizashi has a blade length of 40.3 cm, placing it within the shorter companion sword category. Despite its size, it carries the elegance and authority of a full-length katana. The blade features a deep curvature (sori), which enhances both its aesthetic appeal and functional cutting ability.

The hamon—the hardened temper line along the edge—displays a lively and refined tobiyaki pattern. This complex arrangement of hardened spots demonstrates not only the technical mastery of the smith but also his artistic sensibility. Unlike simple straight hamon, tobiyaki reflects creativity and a willingness to push the limits of controlled hardening.

The steel itself reveals a ko-itame hada, a fine wood-grain surface texture achieved through painstaking folding and forging. Adding to its visual richness is the presence of utsuri, a shimmering reflection-like pattern in the body of the blade. Utsuri is especially admired among connoisseurs as a hallmark of superior craftsmanship and an homage to the great works of earlier swordsmithing schools.

At 446 grams without fittings, the sword is remarkably well balanced, combining lightness with resilience—ideal for a sidearm that might be drawn swiftly in moments of peril.

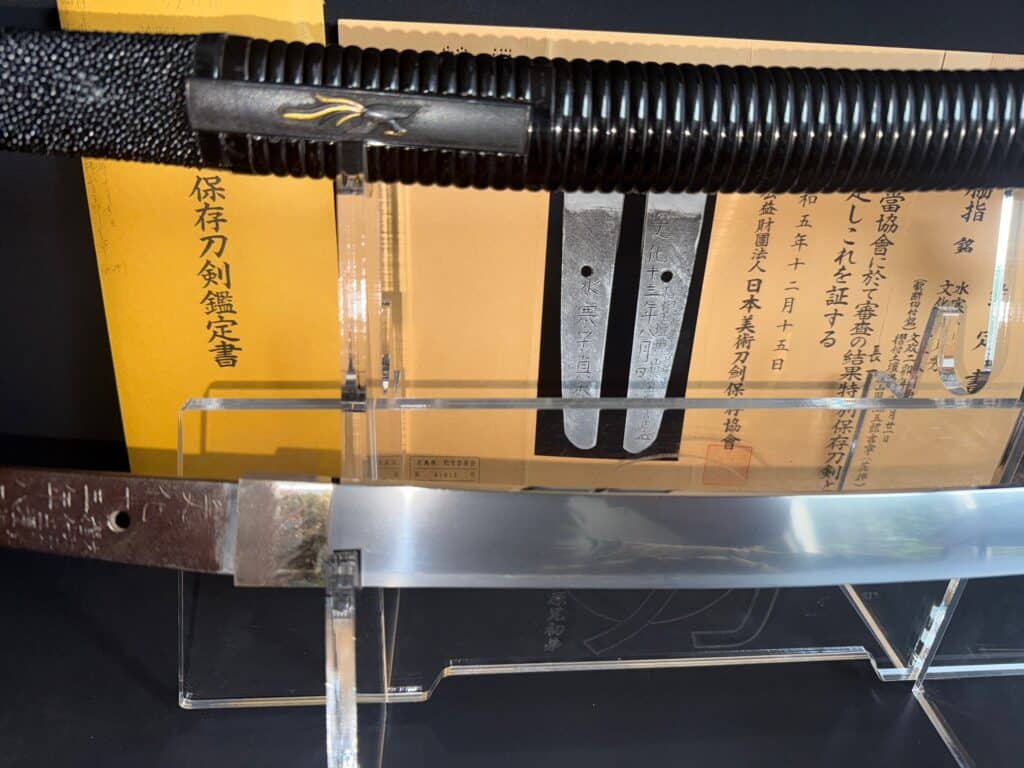

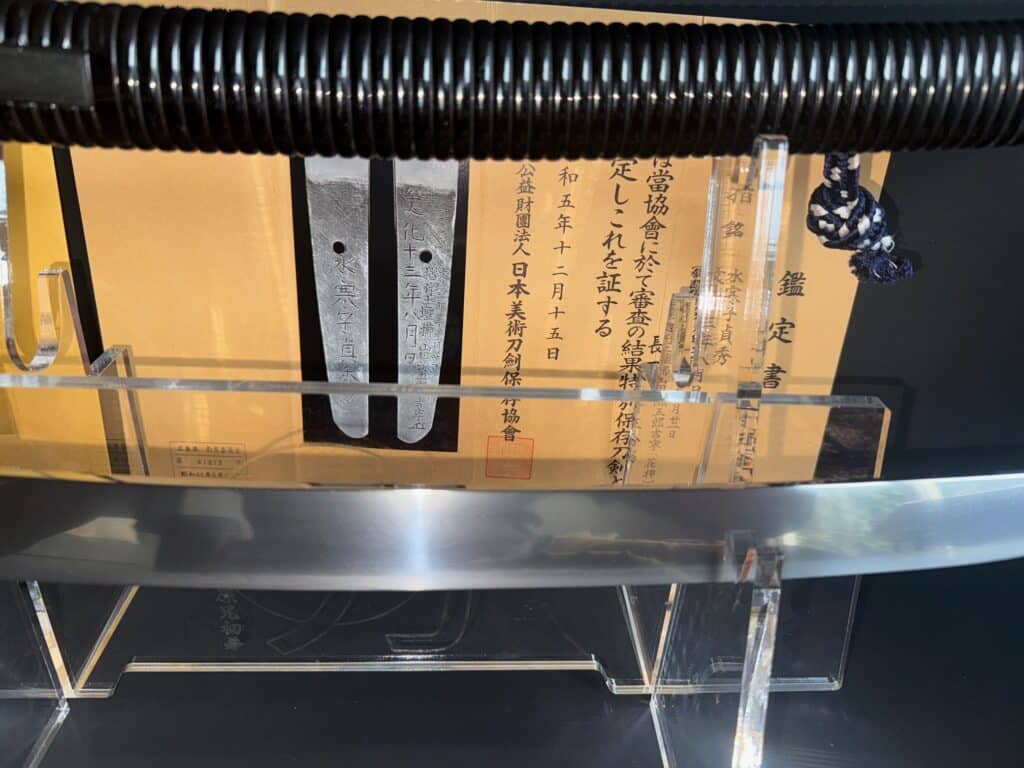

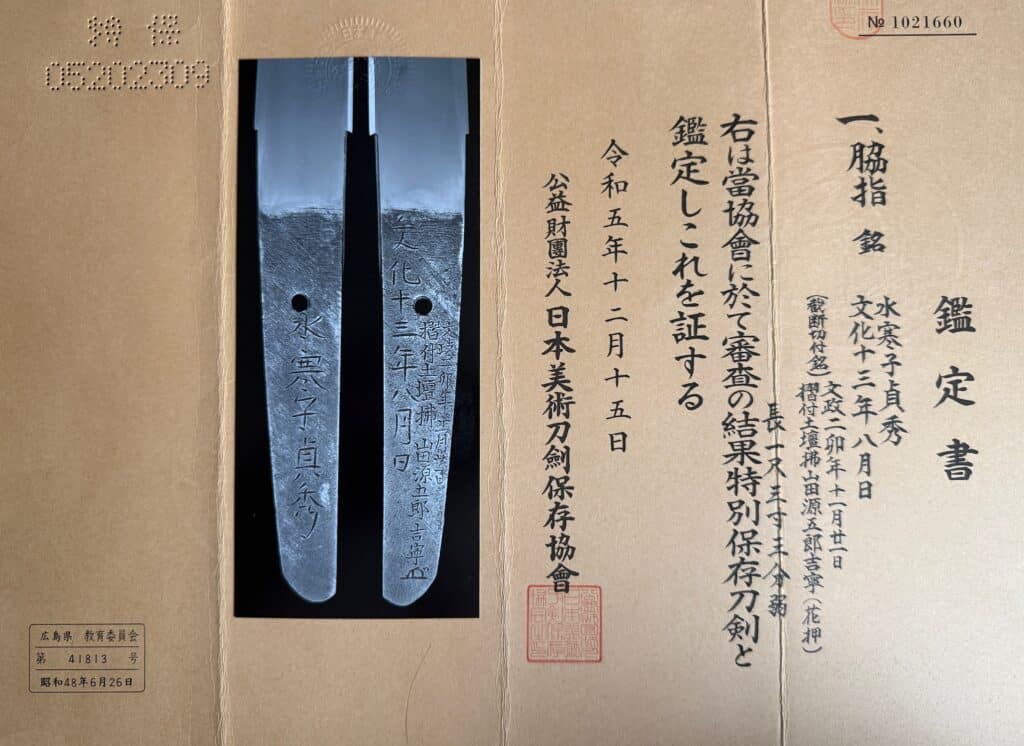

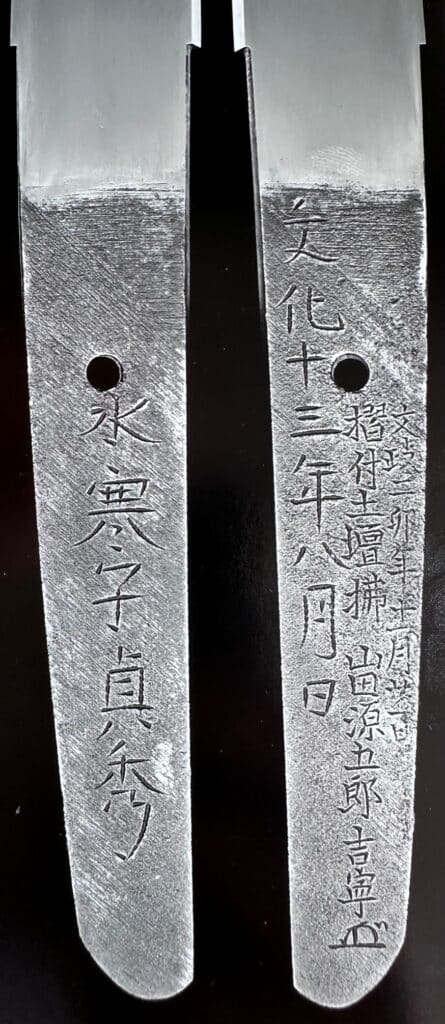

The Body Test by Yamada Gengoro

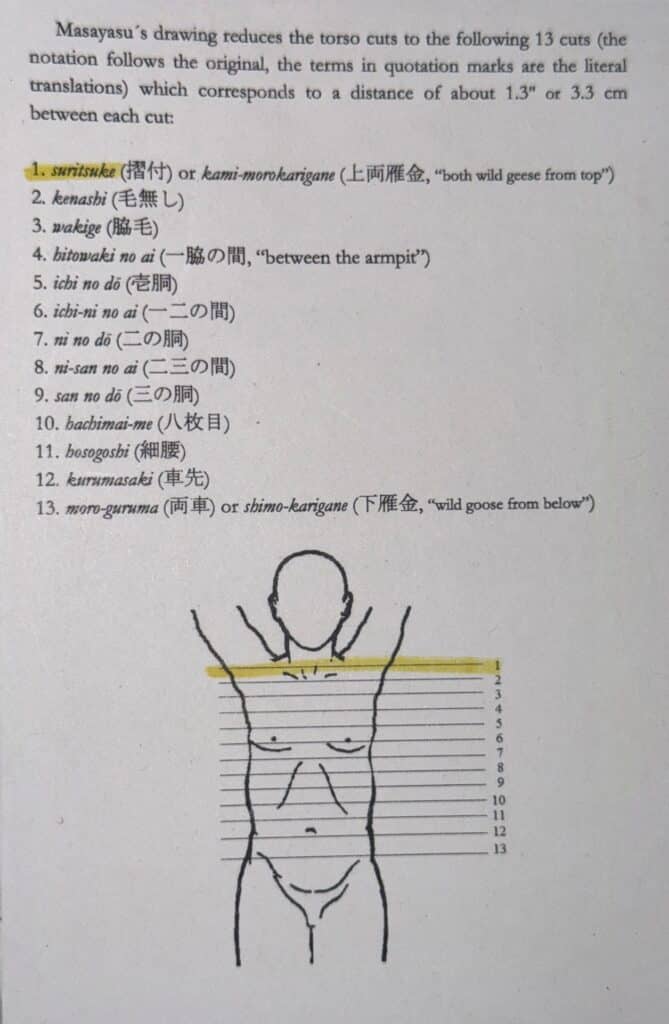

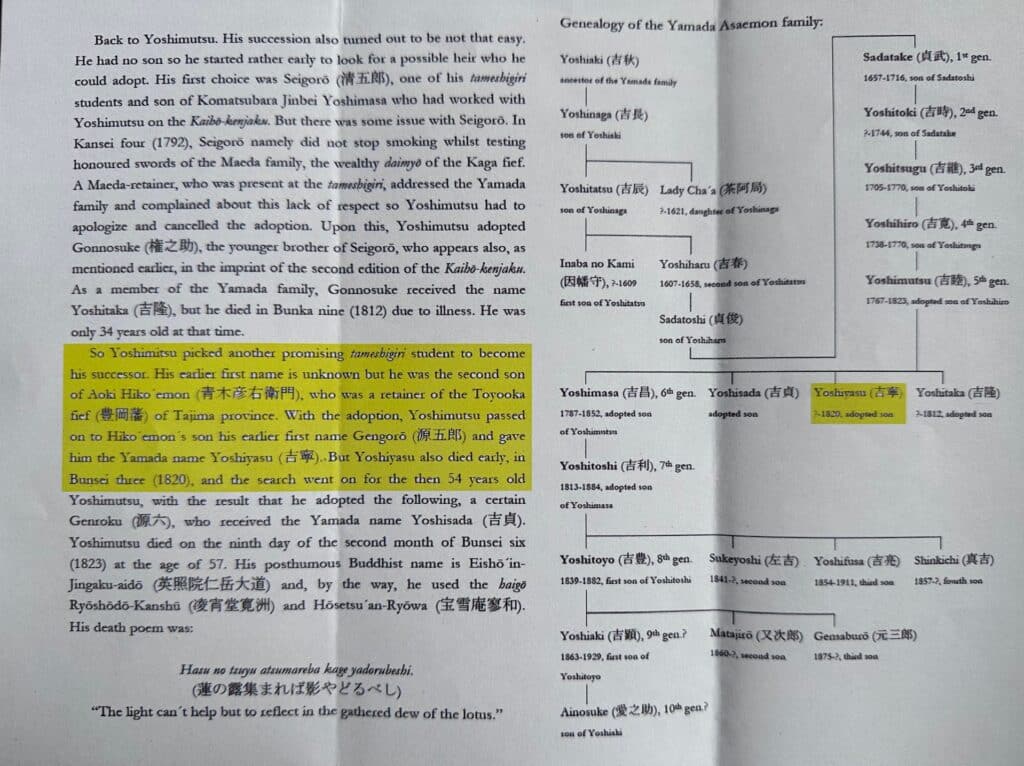

Perhaps the most compelling feature of this Wakizashi is its documented cutting test. In 1819, three years after its forging, the sword was subjected to tameshigiri—formal cutting trials conducted to evaluate sharpness and performance. The tester was Yamada Gengoro, a professional sword tester of considerable reputation.

The test performed was a body cut, an exacting trial that demonstrated the sword’s ability to sever a cadaver in a single stroke. Such tests were not undertaken lightly, as they not only required great skill from the tester but also subjected the blade to severe strain. For a sword to pass and be inscribed with the result was both a mark of honor for the smith and a guarantee of quality for future owners.

The fact that this Wakizashi carries such a record makes it historically exceptional. Few swords survive with authenticated test inscriptions, and those that do are considered highly desirable to both collectors and museums. It situates this piece not only as a work of artistry but as a proven weapon—one that fully embodied the martial ideals of the samurai class.

Certification and Modern Recognition

The enduring importance of this Wakizashi is further confirmed by its certification from the NBTHK (Nihon Bijutsu Token Hozon Kyokai), Japan’s leading authority in sword preservation and appraisal. Awarded the rank of Tokubetsu Hozon (“Especially Worthy of Preservation”), the certificate affirms both its authenticity and its high artistic and historical value. Such recognition ensures the sword’s place among the distinguished works of its era.

Significance for Collectors and Scholars

As a creation of Nidai Suishinshi Masahide (Sadahide), this Wakizashi embodies the spirit of continuity and revival in Japanese swordmaking. It bridges the past and present: rooted in the traditions of Kamakura-style craftsmanship yet created during the peaceful Edo period, when swords were appreciated as cultural treasures.

Its combination of technical brilliance, artistic features, historical documentation of a body test, and modern certification makes it a rare convergence of all the qualities that collectors seek. For scholars, it represents an invaluable case study of Edo-period swordsmithing, linking the philosophies of the Suishinshi school to the lived martial culture of the samurai.

Conclusion

This Wakizashi, forged in 1816 by Nidai Suishinshi Masahide (Sadahide), stands as more than an artifact of steel—it is a living testament to the artistry, discipline, and heritage of Japanese swordsmithing. From its graceful form and intricate patterns to its authenticated cutting trial and official certification, every element underscores its significance. To hold or even to view such a piece is to engage with Japan’s martial past, where the sword was both weapon and symbol, functional tool and cultural masterpiece.