Description

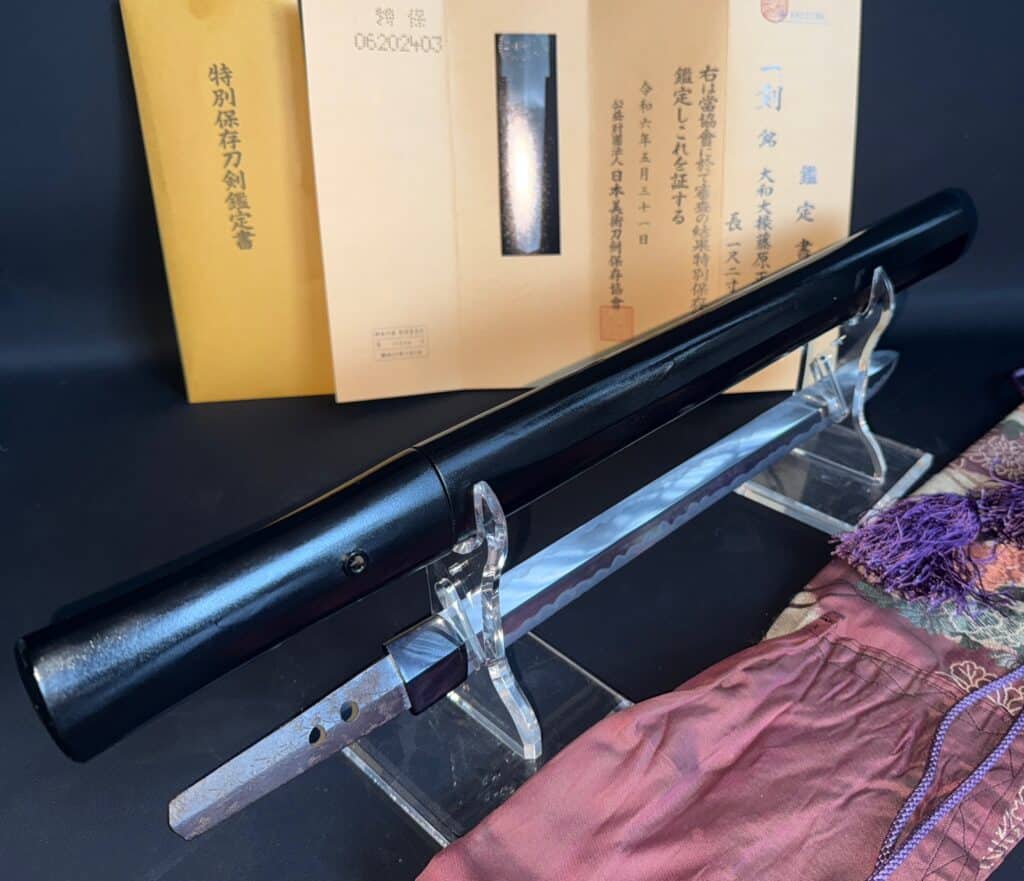

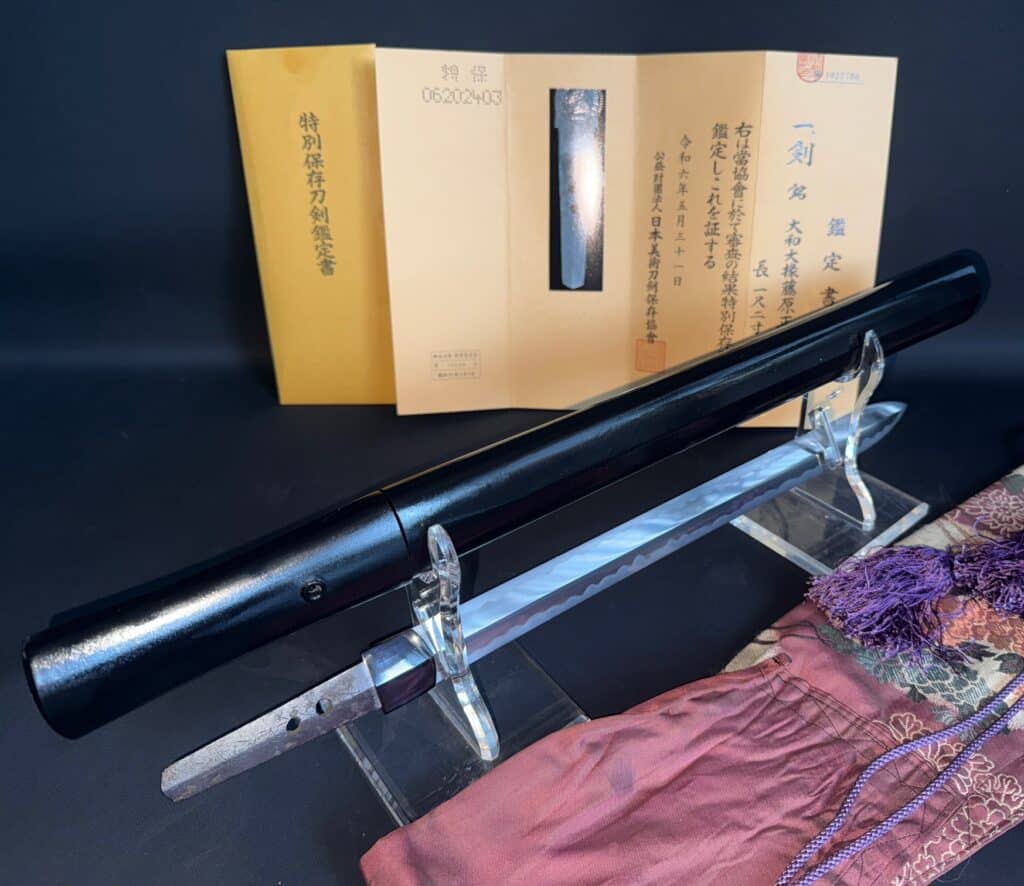

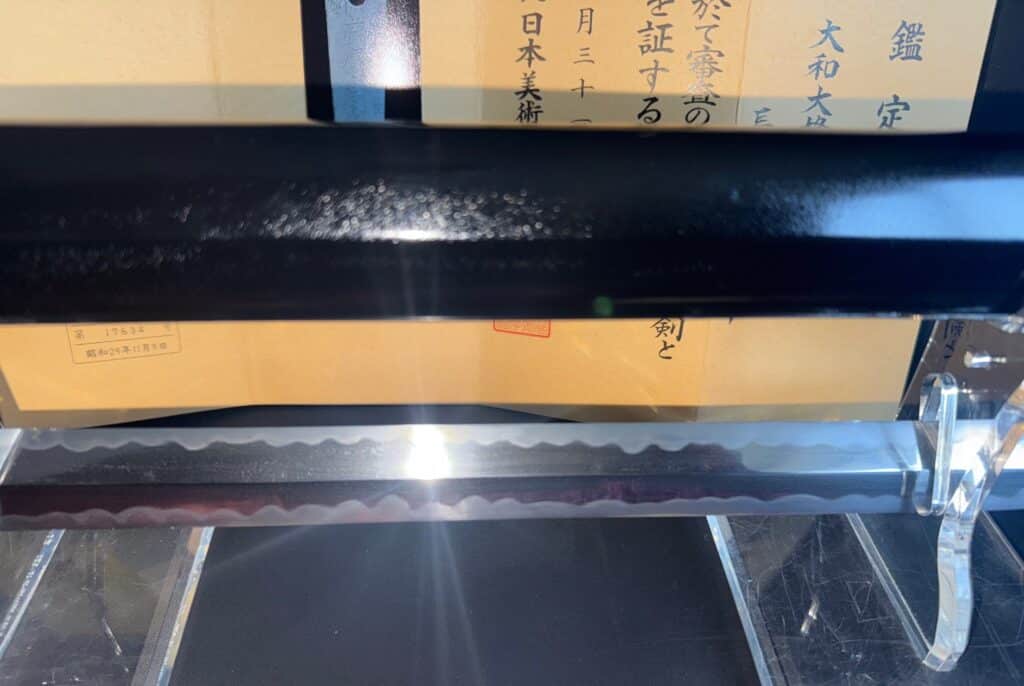

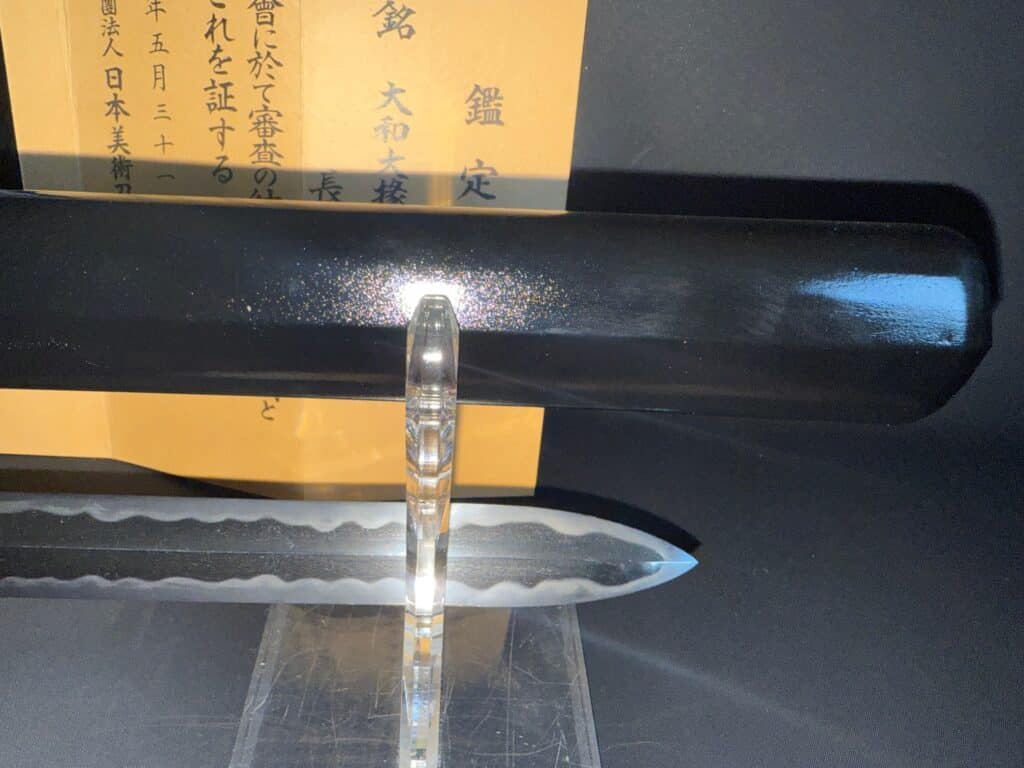

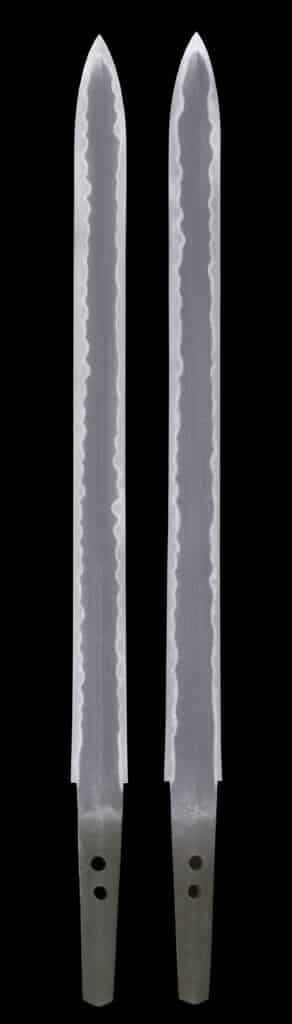

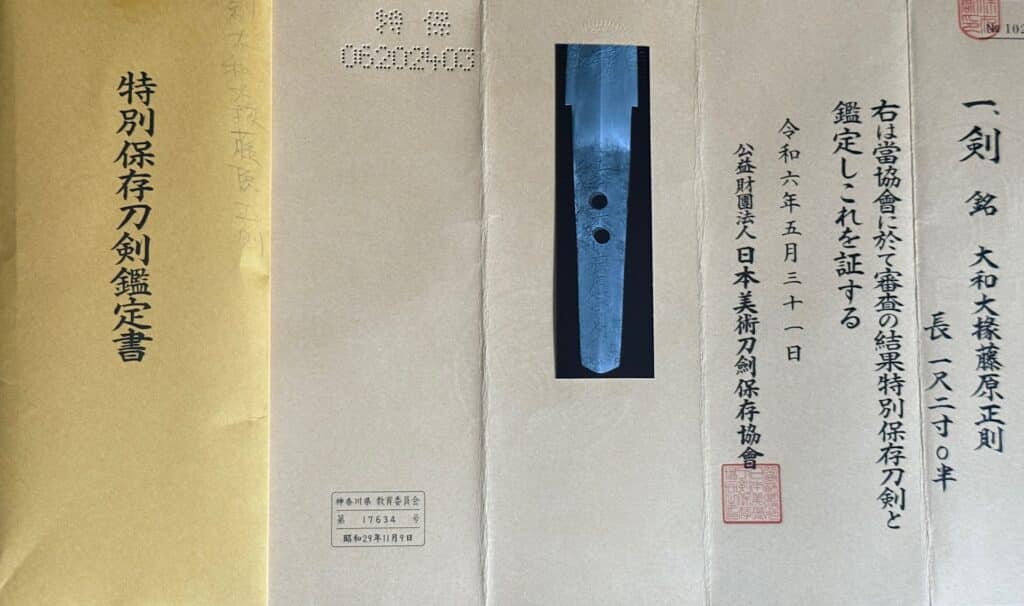

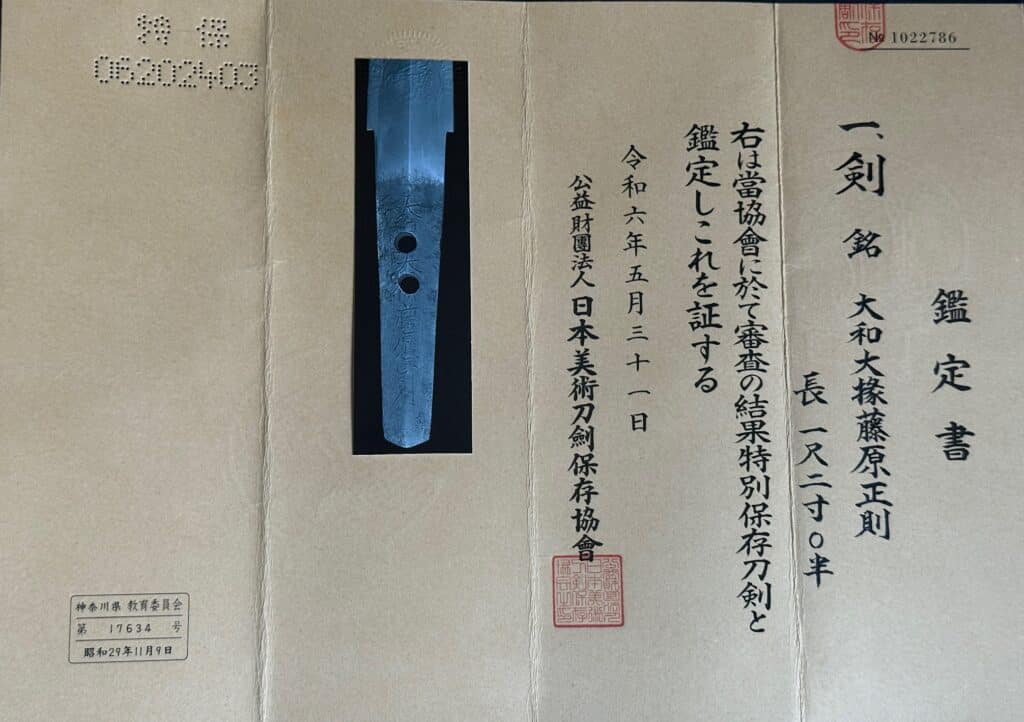

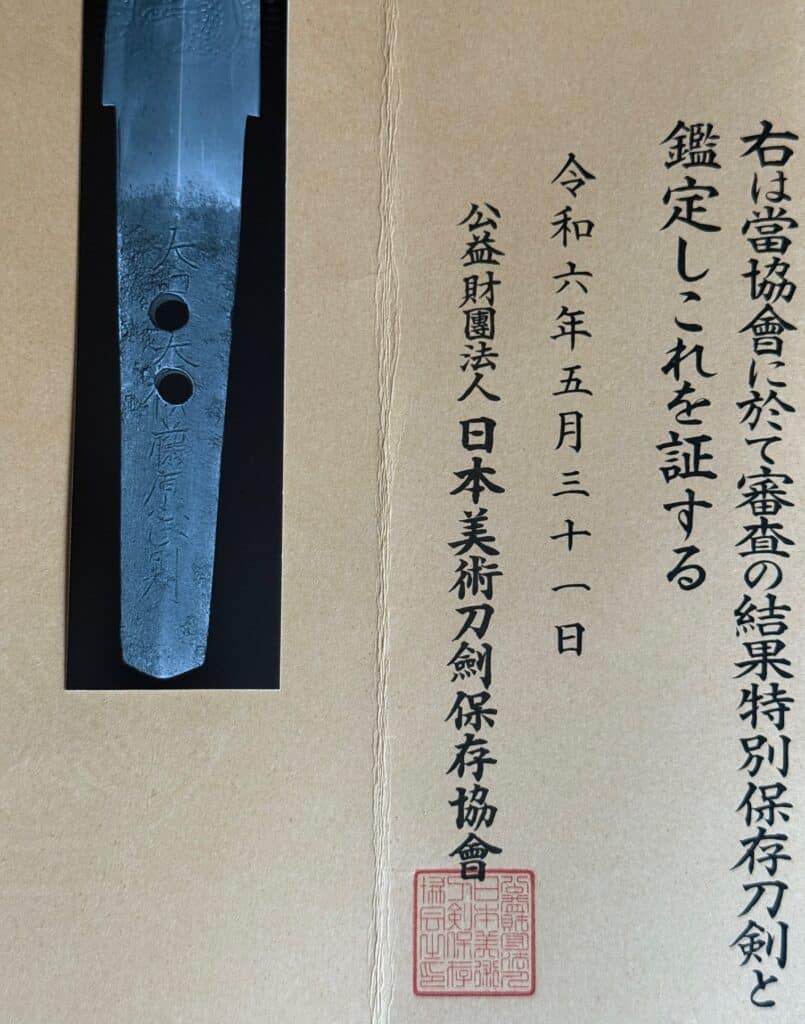

Ken (Tsurugi) by Yamato Daijō Fujiwara Masanori

Certified Special Preservation Sword NBTHK Tokubetsu Hozon

Blade Length: 36.4 cm (1 shaku 2 sun)

Curvature (Sori): 0 cm

Width at Hamachi: 3 cm

Thickness at Kasane: 8 mm

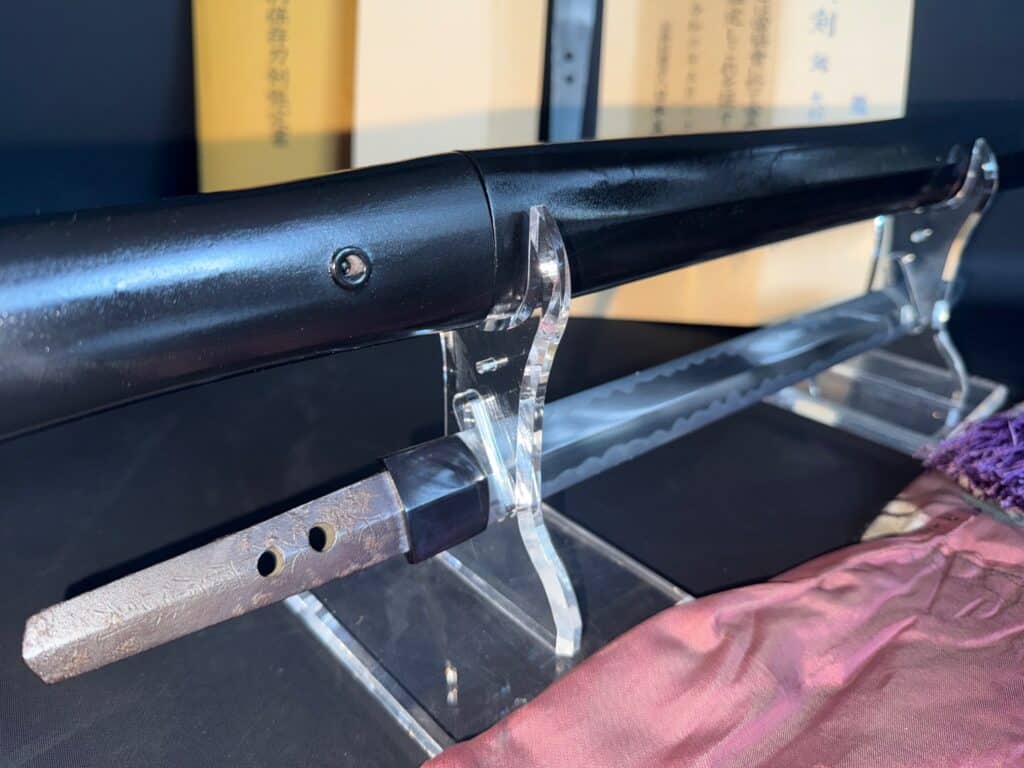

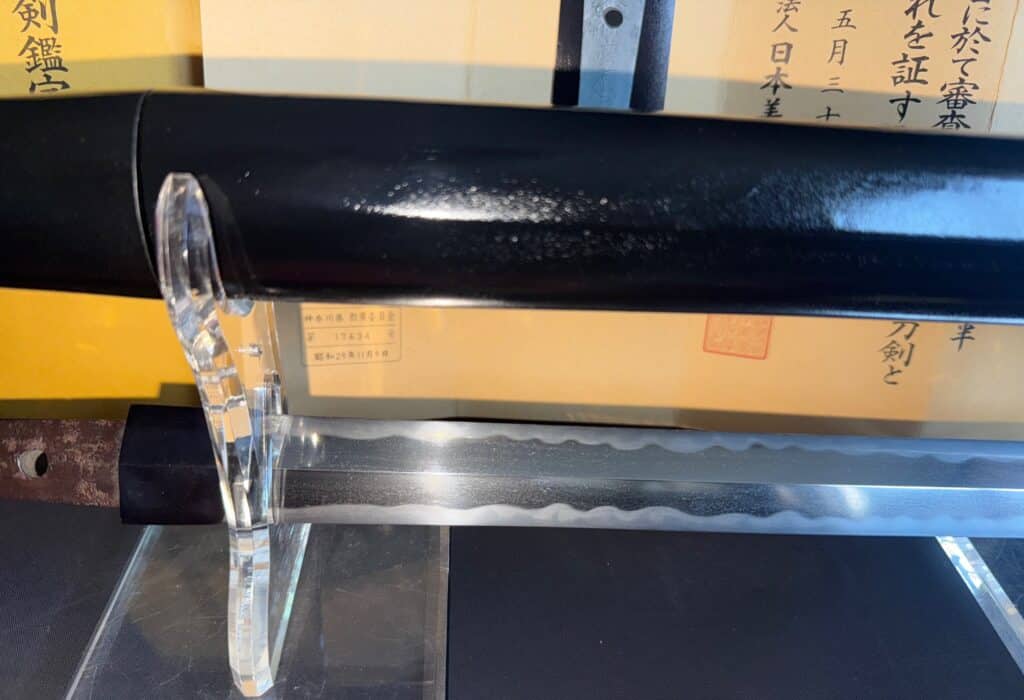

Mekugi-ana: 2

Era: Early Edo period, ca. 1615

Province: Echizen

Historical Background

A tsurugi (剣), also called ken, refers in Japanese tradition to a straight, double-edged sword.

In early antiquity, such weapons carried deep ritual and symbolic meaning, often associated with Shintō shrines and ceremonies, rather than battlefield use. By the Edo period, however, the crafting of ken was less about utility and more about artistry, reverence, and preserving ancient forms.

This fine example was forged by Yamato Daijō Fujiwara Masanori, one of the foremost smiths of early Edo Echizen, and is today preserved with the prestigious NBTHK Tokubetsu Hozon certification, confirming both its authenticity and exceptional cultural importance.

The Swordsmith – Masanori

Masanori was born in Tango Province, descending from the distinguished line of Sanjo Yoshinori. He first trained under his father, Norimitsu, from whom he inherited both skill and a strong grounding in classical swordmaking traditions. His lineage and upbringing prepared him to enter the highest circles of sword production in the early 17th century.

Eventually, Masanori’s path led him to Kyoto, then the flourishing cultural heart of Japan. His talent brought him into the service of Matsudaira Hideyasu, the second son of Tokugawa Ieyasu, who ruled the immense Echizen domain (valued at 750,000 koku). Later, Masanori became the official swordsmith to Hideyasu’s heir, Matsudaira Tadanao, producing blades for the powerful Fukui clan.

In this environment, Masanori fused his Tango heritage with the advanced forging traditions of Echizen. His works embody a distinct balance of durability, elegant shaping, and refined beauty—qualities that soon made his name respected among both warriors and connoisseurs.

Features of the Blade

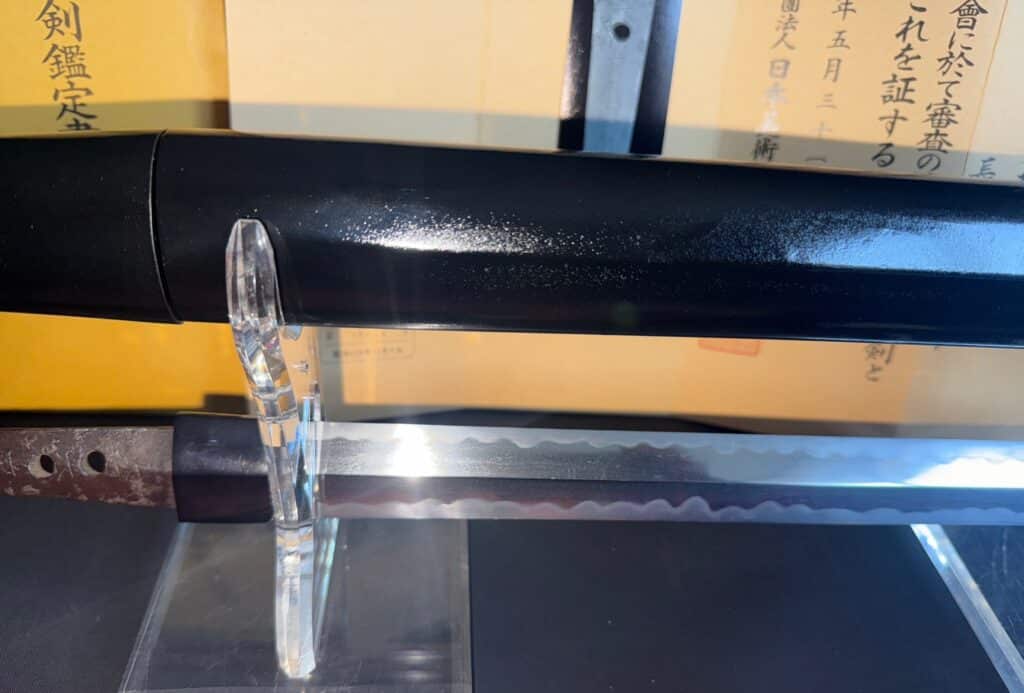

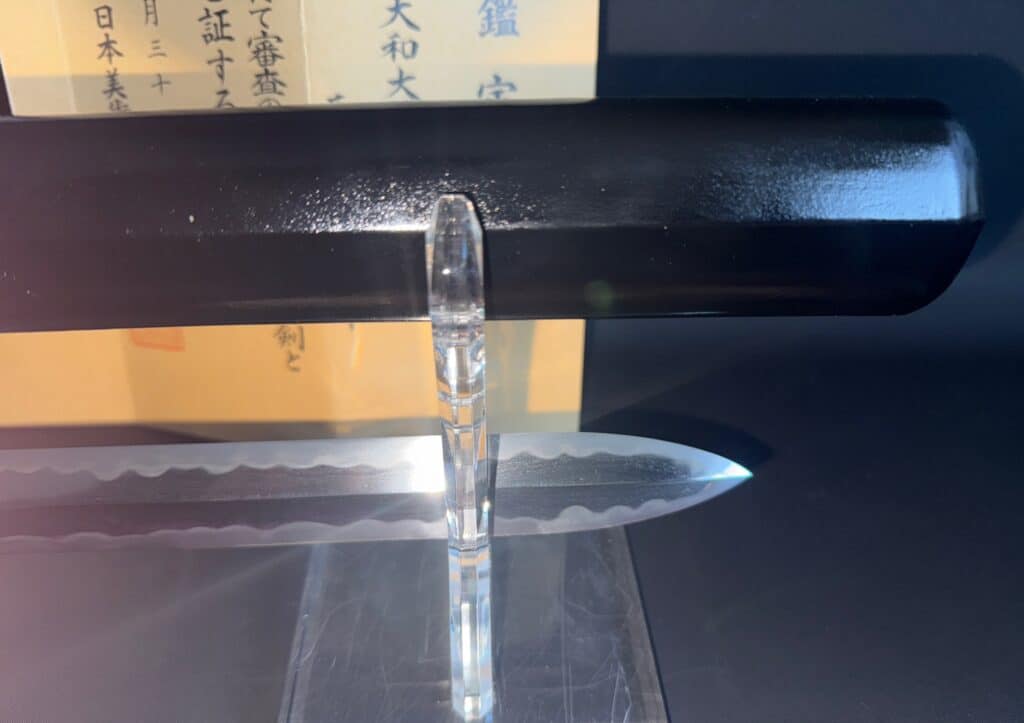

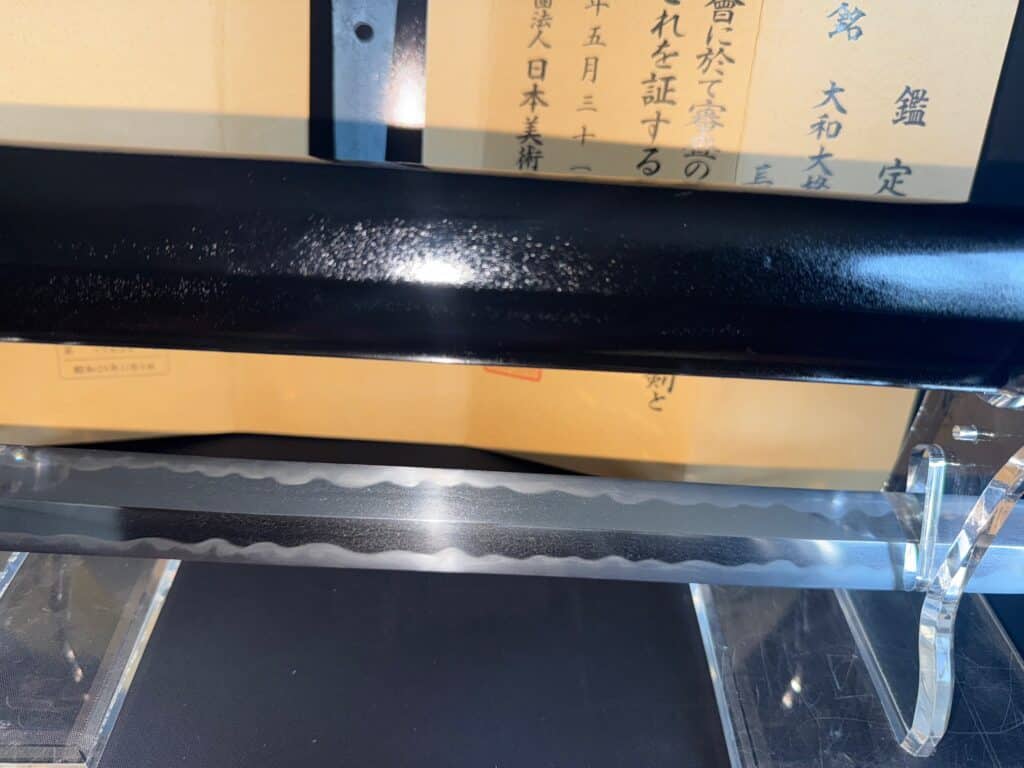

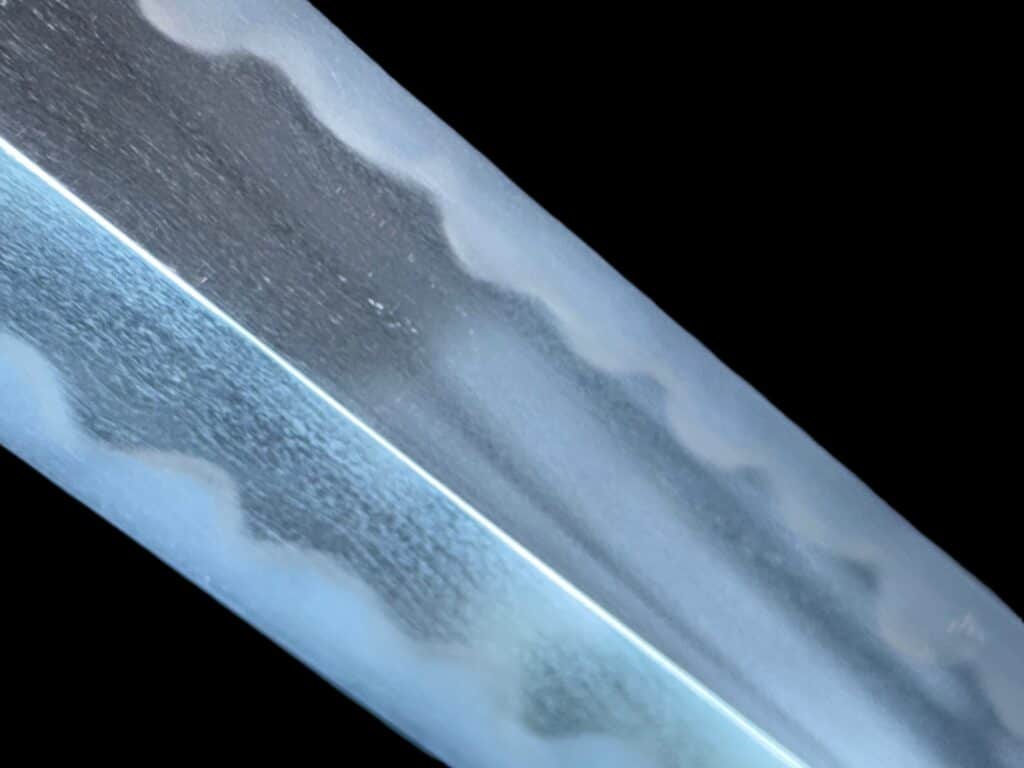

This ken/tsurugi, though compact in size at 36.4 cm, commands attention with its dignified proportions. Unlike curved katana or wakizashi, its straight, double-edged form evokes the earliest sword traditions of Japan. The robust kasane (thickness) of 8 mm and a broad mihaba (width) of 3 cm endow it with a strong and commanding presence.

The absence of curvature (sori: 0 cm) emphasizes its ritual and symbolic purpose, while also showcasing Masanori’s mastery in producing perfectly straight, symmetrical blades—a technical challenge in its own right.

The tang bears two mekugi-ana, indicating that the blade was likely remounted at different stages of its long history, a silent testament to centuries of appreciation and preservation. Despite its age of more than four centuries, the sword remains in excellent condition, its integrity a tribute to both its maker’s skill and the care of generations who safeguarded it.

Legacy and Importance

Swords by Yamato Daijō Fujiwara Masanori are today regarded as rare and highly collectible. Each example represents the transitional moment of the early Edo period, when the turbulence of the Warring States era had given way to Tokugawa stability, allowing swordsmiths to elevate their craft into works of fine art and cultural identity.

Owning such a blade is more than acquiring a weapon it is to hold a tangible link to the Echizen tradition, to the service of the Tokugawa house, and to the enduring craftsmanship of one of Japan’s most respected smiths.

This tsurugi stands as a cultural artifact, bridging the ritual symbolism of Japan’s ancient swords with the refined artistry of the Edo period. It exemplifies Masanori’s skill in combining strength, elegance, and timeless beauty, securing his place among the notable swordsmiths of early modern Japan.