Description

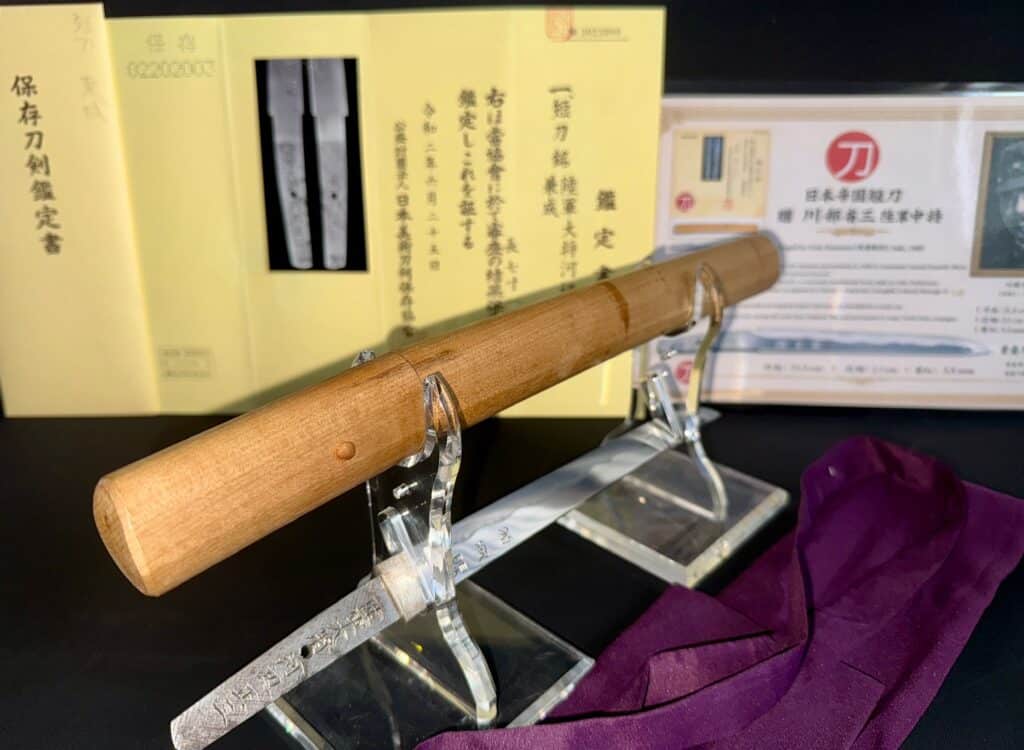

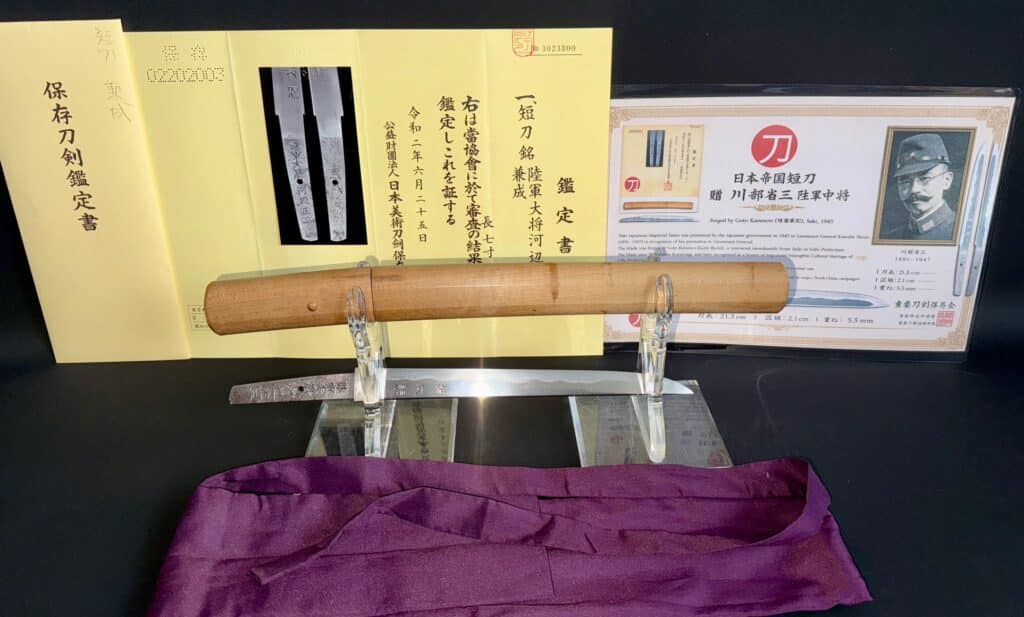

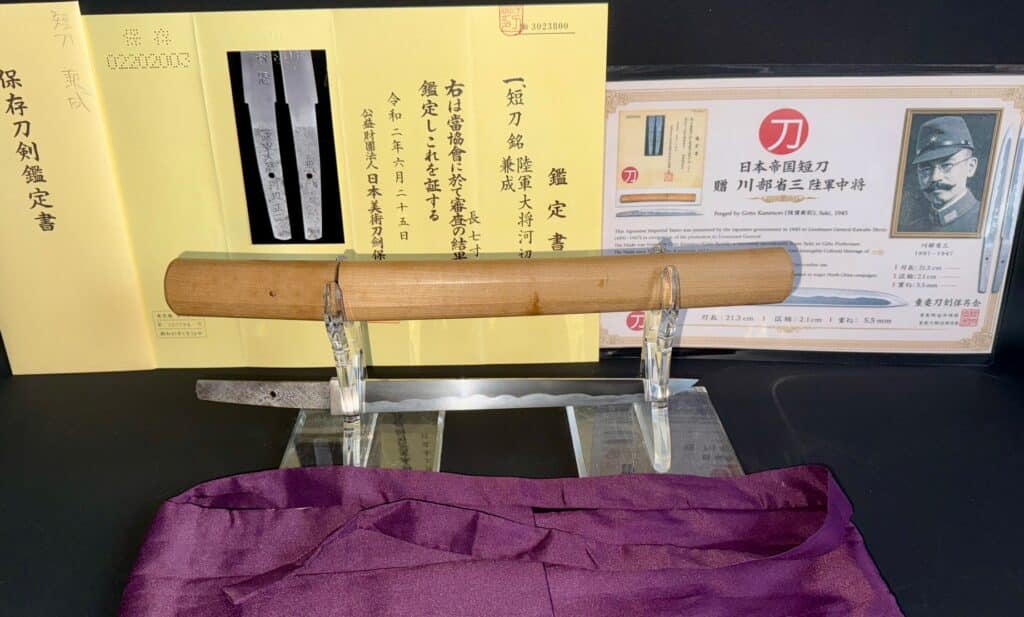

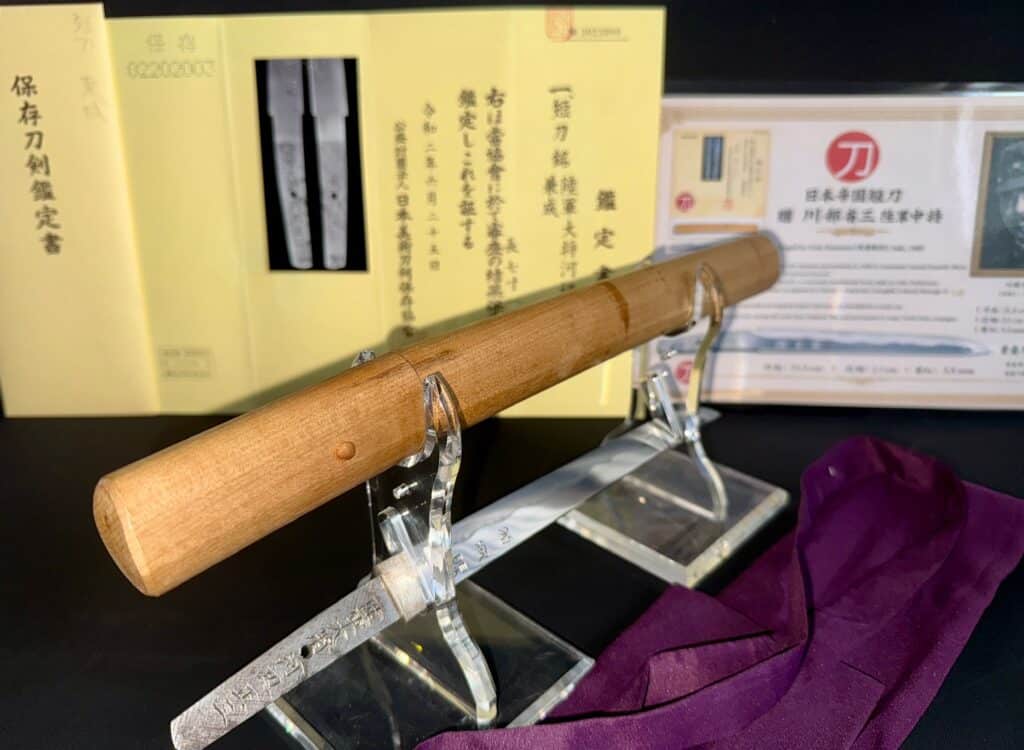

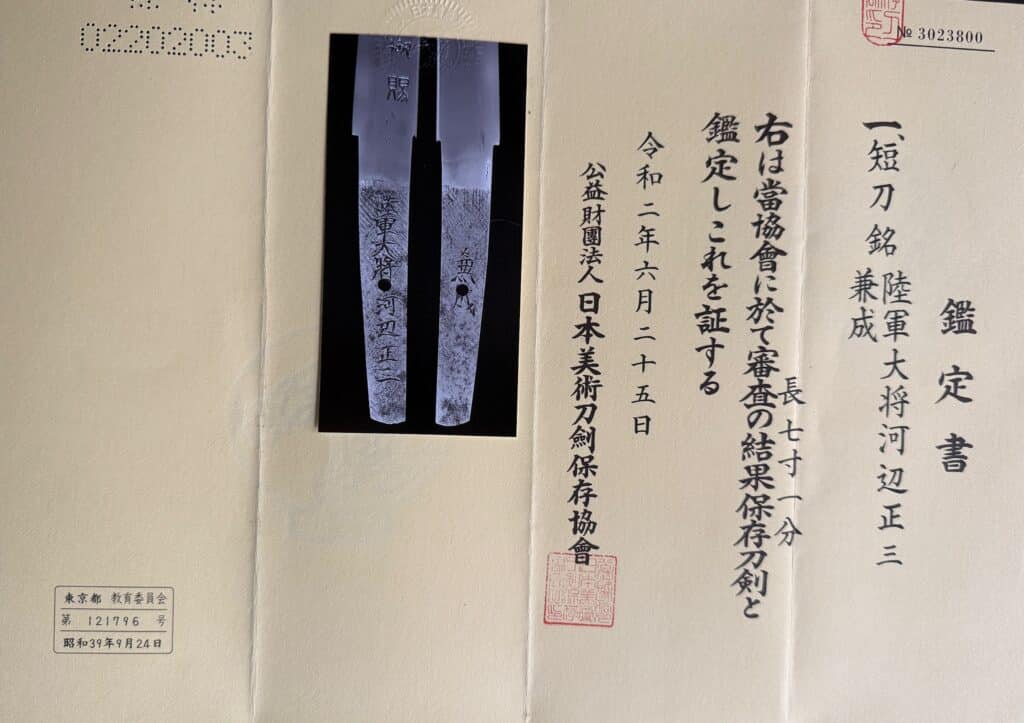

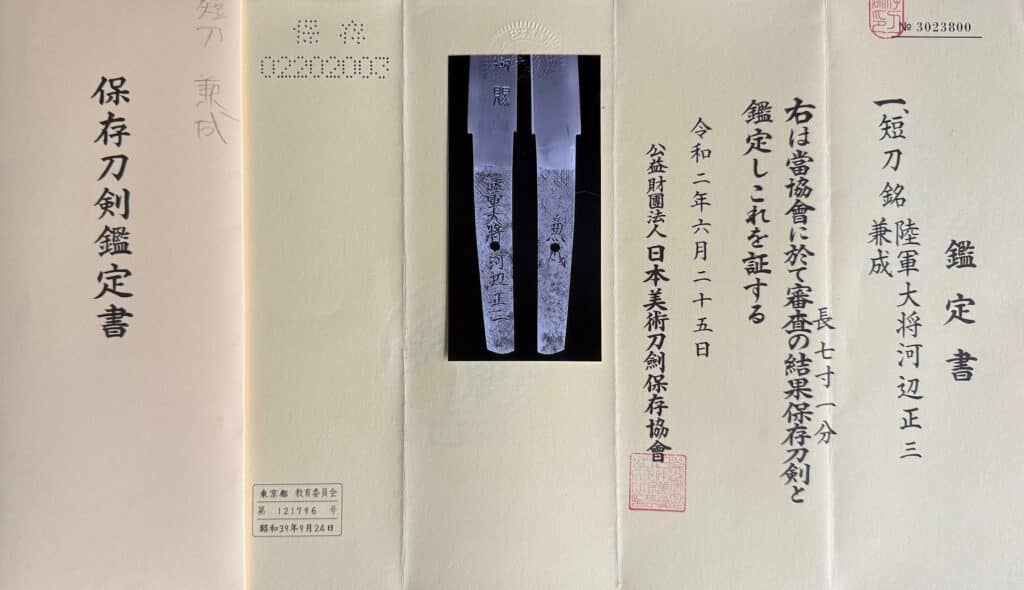

Japanese Imperial Tantō by Gotō Kanenari

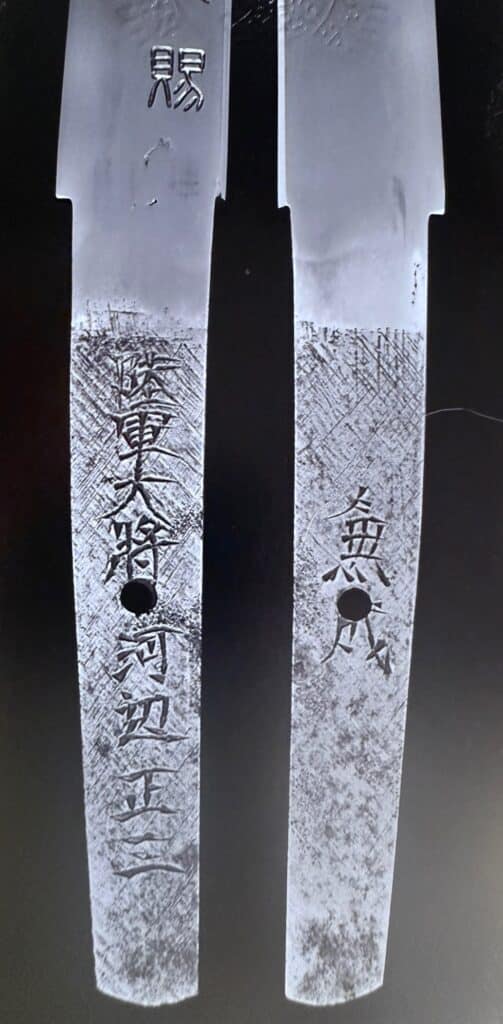

first owner Presented to Lieutenant General Kawabe Shōzō (1945)

This preserved tantō, certified by the NBTHK as Hozon Tōken, is an official imperial Tanto bestowed by the Japanese government in 1945 upon Lieutenant General Kawabe Shōzō (1891–1947). Such presentation blades were ceremonial objects of state, symbolizing rank, authority, and recognition rather than serving any practical military function. Their production marked the continuation of traditional Japanese sword culture even in the final months of the Second World War.

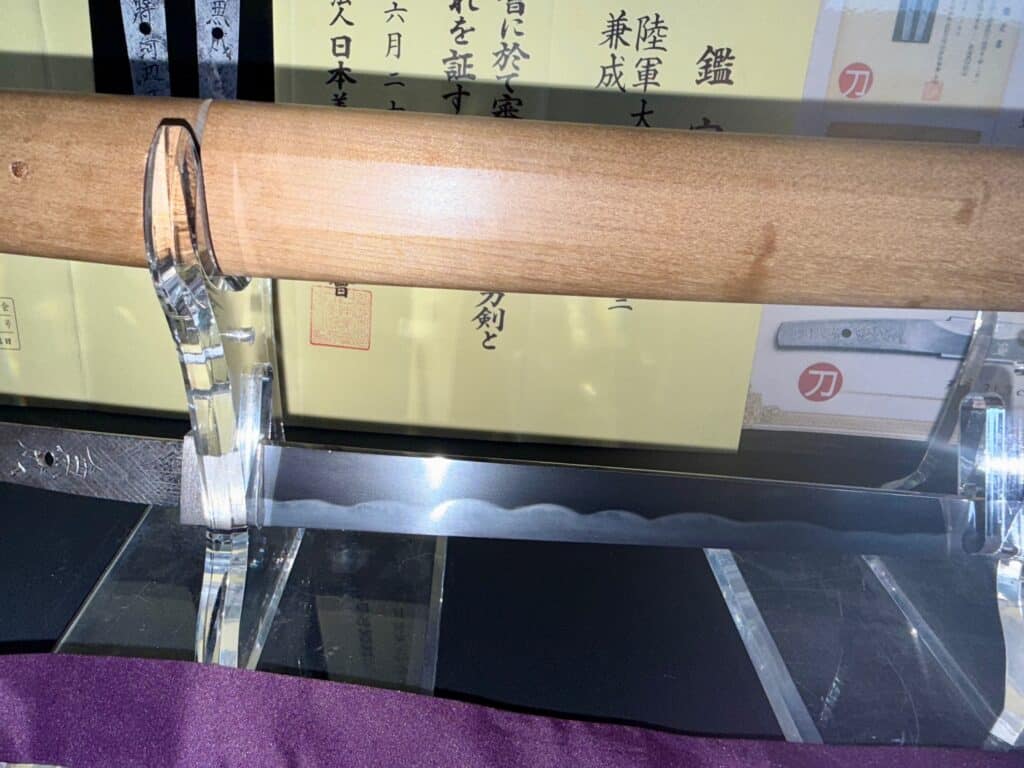

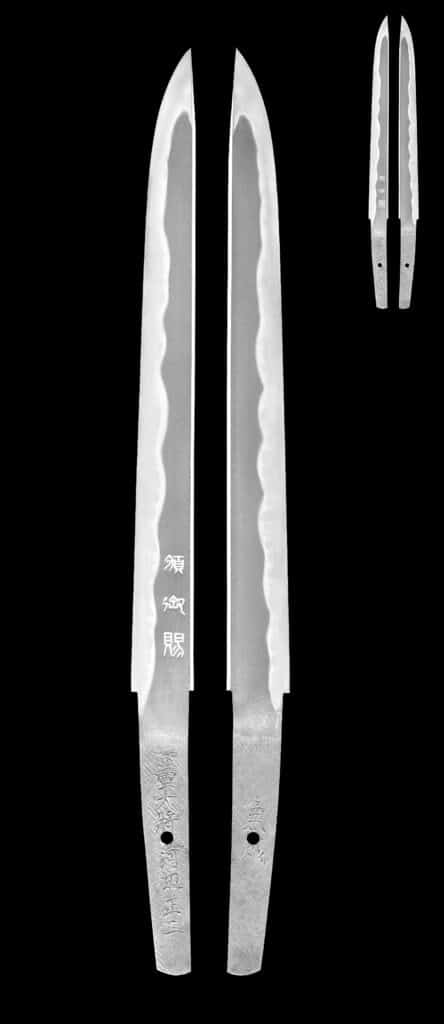

With a blade length of 21.3 cm, a hamachi width of 2.1 cm, and a kasane of 5.5 mm, the tantō follows classical proportions rooted in Edo-period tradition, despite its modern date. The single mekugi-ana confirms it was mounted according to orthodox Japanese sword construction. Although forged in 1945, the blade consciously reflects earlier aesthetic ideals, illustrating how ceremonial swords remained bound to historical forms even as Japan faced imminent defeat.

The Swordsmith: Gotō Kanenari (後藤兼成)

The maker of this tantō, Gotō Kanenari, was the art name of Gotō Ryōzō, born in 1926 in Seki City, Gifu Prefecture a region internationally renowned for sword production since the Kamakura period. He studied under Watanabe Kanenaga, a respected swordsmith known for preserving classical forging methods during the Shōwa period.

Kanenari would later be recognized as a bearer of Important Intangible Cultural Heritage of Gifu Prefecture, reflecting his role in maintaining traditional Japanese metalworking and sword-forging techniques. Although still young at the time this blade was forged, his work already demonstrates disciplined craftsmanship, balanced geometry, and a strong grounding in classical sword aesthetics. This tantō stands as an early but historically significant example of his work, created at a moment when traditional craftsmanship intersected with state ceremony and military hierarchy.

Kawabe Shōzō: Military Career and Historical Role

Kawabe Shōzō (河辺正三) was born in 1891 and pursued a career as a professional military officer in the Imperial Japanese Army. Rising steadily through the ranks, he eventually attained the position of Lieutenant General, holding senior command roles during Japan’s military expansion in East Asia.

Kawabe played a significant role in the events surrounding the July 7th Incident of 1937, also known as the Marco Polo Bridge Incident, which marked the beginning of full-scale war between Japan and China. At that time, he was directly involved in command operations on the North China Front, serving as a key officer within the Japanese 5th Division.

During the initial phase of the conflict, Kawabe participated in the planning and execution of major military operations, including the attacks on Lugouqiao (Marco Polo Bridge) and Wanping Fortress. He worked alongside senior figures such as Sugiyama Hajime, Minami Jirō, Tashiro Kanichirō, and Kazuki Kiyoshi, contributing to coordinated operations aimed at securing strategic control over northern China.

Under his command and influence, Japanese forces took part in several major engagements, including the Battle of Beiping (Beijing), the Battle of Tianjin, and the Battle of Taiyuan. These campaigns were instrumental in Japan’s rapid military advance but also resulted in widespread destruction, civilian suffering, and long-lasting consequences for the Chinese population. Kawabe’s role places him among the senior military figures responsible for the execution of Japan’s wartime strategy in the region.

By 1945, as the Pacific War reached its final phase, Kawabe was promoted and formally recognized by the Japanzstazze. It was on this occasion that this bestowed upon him. Such ceremonial swords were traditionally granted to senior officers as tangible symbols of imperial favor, loyalty, and service to the state.

The act of presenting a sword particularly a tantō carried deep cultural meaning in Japan. Even in the modern era, the sword remained a powerful emblem of authority, discipline, and continuity with the samurai tradition. That such an object was commissioned and presented in 1945 underscores how symbolic practices persisted despite Japan’s rapidly deteriorating military situation.

Historical and Ethical Context

Following Japan’s surrender in August 1945, Kawabe Shōzō’s military career came to an end. He died in 1947, only two years after receiving this presentation blade. His legacy, like that of many senior officers of the Imperial Japanese Army, is inseparable from the broader history of Japan’s wartime aggression in East Asia.

Today, this tantō must be understood not as a celebration of military achievement, but as a historical artifact—one that embodies both the refined artistry of Japanese sword-making and the complex, often troubling history of the era in which it was produced. The blade serves as material evidence of how traditional craftsmanship was employed within systems of political power and military authority.

Significance

This imperial presentation tantō is a rare and historically charged object. It unites three distinct narratives:

-

the preservation of classical Japanese sword-making,

-

the ceremonial culture of the modern Japanese military state, and

-

the personal history of a senior officer involved in pivotal wartime events.

As such, it is best suited for museum collections, academic study, or advanced private collections, where it can be interpreted with appropriate historical awareness. Viewed in this context, the tantō stands as a silent witness—crafted in steel—to a decisive and consequential chapter in twentieth-century history.